Loop Raccord (2010)

April 28, 2011 - Features

“I see storytelling as a game: whenever I am making a film, a book or a comic, I set a series of rules for myself and I try to play with them to reach their limits. Watching a movie or reading a book is not a passive experience.

The viewer/reader can perceive those rules if he feels that they are set for him, and he can play with you, trying to decode them to anticipate the author, and be surprised and amused whenever he cannot.

So in many senses, even if I have no specific game-making background, I feel like I’ve been making games for a while.”

In a recent post, I talked a bit about my love for experimental film and how that influences the way I see experimental games. So I was pretty excited when I came across Nicolai Troshinsky’s Loop Raccord while catching up on experimental games. Loop Raccord was one of the finalists for the Nuovo Award at this year’s Independent Game Festival. The nominees make an impressively diverse lineup that says good things about where experimental gaming is right now. But I found Loop Raccord especially charming.

The game is inspired by found footage work like Virgil Widrich’s Fast Film, where pieces of film from existing movies are edited together in new combinations. When making such a film, one thing an editor may want to do is find some harmony of movement between two dissimilar clips, spliced back to back. Loop Raccord turns the process of searching for that movement harmony into a simple puzzle game. Each level is a grid made up of short found-footage clips, each of which contains some movement through the frame.

The player’s job is to match the timing of the clips one at a time to create a continuous path through the grid. At each stage, there is a leading clip whose movement you are meant to match, and an active clip that you can pause and scroll through to set up the timing. The game scores your raccords based on how precisely timed they are.

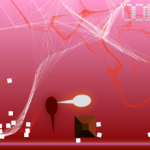

I eventually got the hang of finding perfect raccords, usually by focusing on the leading clip rather than the active clip. But there was one combination of clips that absolutely threw me. It’s shown in the screenshot above. The leading clip features a man slamming what looks like the trunk of a car closed, and the active clip is a boy sitting down while someone closes a door in the background. And try as I might, I could not force myself to sync the two clips in terms of motion. Every single time, entirely against my will, I synced them so that the two doors shut at the same time. Even when I realized what I was doing, I couldn’t stop myself. I was only able to pass the stage by clicking randomly on the active clip until it lined up by chance.

It seems like Troshinsky is interested in such puzzles of perception. Another one of his games, Motion Columns, is a match-3 game in which you match items in terms of motion patterns instead of color or shape. It’s phenomenally difficult. In the description, Troshinsky suggests looking slightly away from the game screen, in order to use the superior motion detection of your peripheral vision to pick out the patterns. These are games that push the player to struggle against her customary modes of perception. When you get a few good raccords in a row, you start to see the film clips in a different way. You abstract them into motion patterns, and for a little while, you stop seeing the man, or the door, or the words. Just like you have to stop seeing the colors to get into the flow of Motion Columns. But these states are fragile. If you screw up, the colors and the people overload your senses once again.

The terrific quote that starts this post is from an interview with Troshinsky by IndieGames.com. I’ll probably write more about it later. For now, I’ll just note that a lot of resistence to experimental film, and other experimental forms, comes from the viewer not knowing that they are expected to play along. I suppose that gives art games a little bit of an advantage.