The Wrong Ending

November 15, 2011 - Features / Tragic Ends

So the blog’s been a bit on the sporadic side lately and, in all honesty, it probably will be until after Thanksgiving. My apologies! On the upside, something pretty grand has been happening while I was away. Dan Cox of Digital Ephemera, with the help of commenter Ari, has taken some rough ideas in my post on Moral Incentives and Story Structure and made something terrific out of them. In a series of posts at his blog, Dan and Ari have been seriously tackling a question that I raised sort of tangentially: can a videogame be a tragedy? If so, how would you design such a game?

Some highlights from this rich discussion include What Happens Next, in which Dan takes on the issue of asymmetrical knowledge in tragedies, game-based or otherwise; Tragedy Drivers, which discusses some of the design constraints on a tragic game; and Flaws in Virtual Tragedy, which directly applies concepts from Aristotle’s Poetics to the debate. It’s all awesome stuff, go read it. A lot of what we’ve been talking about so far, both at Digital Ephemera and here, boils down to how interactivity philosophically clashes with the basic assumptions of tragedy as Aristotle saw them. I’d like to jump off Dan’s thoughts on asymmetrical knowledge and talk about some of the practical issues with designing tragic games.

To start with, let’s lay out some basic premises about tragedy in games:

- The emotional impact of tragedy comes from a cosmic punishment of an essentially sympathetic protagonist’s fatal flaw.

- In games, punishment of the protagonist lacks impact unless the player is punished as well.

- Players tend to optimize systems, all else being equal.

Premise #1 comes from Aristotle, basically. Premises #2 and #3 are perhaps more arguable, and are certainly not universal. However, they do represent important general differences between game players and other sorts of audiences.

When you take these three premises together, you start to see some of the problems that games have with presenting tragedy in a meaningful way. You can have something tragic happen to the protagonist without any consequences for the player, as in Shadow of the Colossus. Your feeling of hard-earned victory contrasted with Wander’s inevitable downfall creates a dissonance between the player and the avatar that Colossus uses to great effect, but it isn’t quite the same thing as classical tragedy. The effect on the audience of classical tragedy derives from sympathy with the protagonist; if you and the protagonist are pulling in different directions, this effect can’t be recreated.

The solution, then, is to punish the player as well as the protagonist. But how do you do this? You can’t just change the emotional tone of a cutscene and call that punishing the player. The player is in this for engagement, and sad things can be just as engaging as happy things. To punish the player meaningfully, you have to affect gameplay. You can take resources away, forcing the player to change her strategy. You can take content away, so that the player sees less of the story or game world under certain circumstances. You can make the game more difficult (which may be a punishment or a reward, depending on the player). You can make the player’s quest goals go unfulfilled. There’s a lot you can do, and many games have tried these tactics and others.

That said, as Dan points out, if something bad inevitably happens to the player, there’s no cosmic punishment. For the full tragic effect, the downfall has to be a consequence of the hero’s flaw or mistake. There needed to be a point where the downfall could have been avoided. But as soon as that’s the case, premise #3 jumps in and ruins everything: if there’s a sequence of events where the player gets less stuff, however stuff is defined, players will always view that sequence as “wrong.” This is a common complaint in RPGs with morality systems: usually, being a dick means you take on fewer quests, so why would you want to be a dick? If you get punished for some behavior in a game, well, that wasn’t what you were supposed to do. To optimize the system, you have to avoid the mistake.

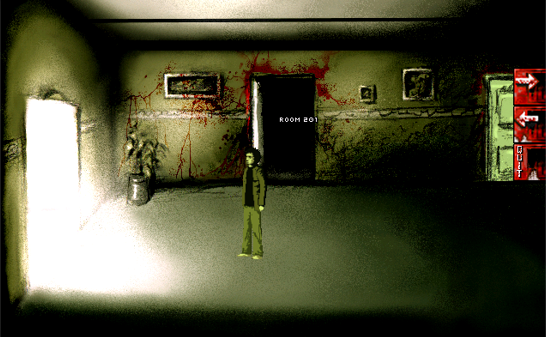

It’s not that players won’t sometimes pursue a “wrong” path, for kicks or to get an achievement or to see different versions of the story. The problem is that their reasons for doing so have a tendency to be lighthearted, precisely because the path seems wrong to them. It’s a diversion on the way to to the correct ending. Dan’s post describes a common experience with Mass Effect 2, in which the player initially gets an ending where several team members die and later goes back for a second playthrough where the team survives. Since this ending will be imported into Mass Effect 3, getting it right is particularly important to many players.

That sense that the happy ending is the one where you got things right is pervasive in games stories – and really, in how we talk about other kinds of stories as well. Indeed, much of the emotional impact of a tragedy comes from the audience’s perception of other, better paths the hero could have taken. If only Lear had trusted Cordelia. If only Romeo and Juliet had coordinated their plans better. If only, then things would have turned out right. The line between tragedy and comedy (in the classical sense) is often one false move or twist of fate, and both the relief of a happy ending and the anguish of a tragic ending come from the audience’s knowledge of the other turn the story could have taken. Tragedy is the wrong ending.

So how do you get a player to pick the wrong ending? More importantly, how do you get her to do that and still care?

I’ll take that question up in a subsequent post. For now, I’ll leave it at this: the trick is to get the player to be willing to go down the wrong path, with the right path still in sight. Getting that to work is a balancing act that few games have figured out how to pull off.