Line on Sierra: Quest for Glory I, Part 1

March 12, 2018 - Line On Sierra

Ten games into this series, I’ve started to get the hang once more of how Sierra games work. So it’s the perfect time for a game to come along that doesn’t work like any of the others I’ve played so far.

To be fair, I’ve been surprised by the amount of variation I’ve encountered in how different designers made use of the early Sierra game engines. But Quest for Glory, originally known as Hero’s Quest before a copyright dispute, is the first attempt to make a genuinely different genre experience using tools made for adventure games. Director Lori Ann Cole has discussed how her team’s intent was explicitly to introduce elements of tabletop and computer roleplaying games to adventure game players. The result combines the wandering-in-a-big-field structure of a King’s Quest game with an extensive skill-based gating system reminiscent of a stat-driven visual novel like Long Live the Queen. And then there’s arcade-y fights. Oh my god, so many fights. And even more running away from fights.

There’s a lot of moving parts to this thing, is what I’m saying. There are multiple ways to approach your character’s goals and lots of different kinds of obstacles to achieving those goals. So my path through Quest for Glory isn’t necessarily the same as anyone else’s, no matter how hard I hit the walkthrough.

What follows is the story of a man who fails in nearly every way possible before pulling the unwieldy system of his life together just enough to lurch over the finish line. And since I let Twitter name my character, it’s the story of a man named Hamburger Tree.

WHAT IS EVEN HAPPENING

The gleefully thin backstory of Quest for Glory: you are a young adventurer who learned how to be a hero from a correspondence school. You have now arrived at the embarrassingly named village of Spielburg to ply your trade. And that’s it, that’s all you get. Go for it, kid. According to Cole, keeping the character’s backstory open was intended to encourage players to define their own story, which is also the reason the game is so open-ended. In that spirit, my backstory for Hamburger Tree is that he emerged fully-grown from a walnut in Daventry and has no idea how human society works. Kind of a self-insert, I know.

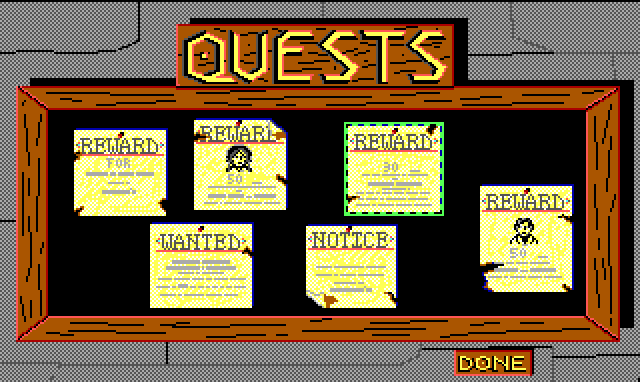

There’s not a whole lot going on in the village. There’s a sheriff who delivers a big exposition dump, a few stores selling stuff you can’t immediately afford, a bar where everyone is mean to you, and an Adventurer’s Guild Hall. The Guild Hall is where you pick up the bulk of the story, in the form of a bunch of posted quests.

It turns out there are three big problems in the valley of Spielburg: The baron’s daughter is missing, the baron’s son is also missing, and there are some bandits. These all have big rewards, so you can tell they’re the main questline. You can follow up on them by going to the baron’s castle and getting shouted at by a guard. It seems that the whole region has gone to hell after this series of kidnapping crises and no one is around to help out. (The Adventurer’s Guild is staffed by a single sleepy old man.)

This investigation didn’t flesh out the storyline much, but at least it gave me an opportunity to see what’s outside the village: namely, the baron’s castle and a big sprawling wilderness. The map is larger than most of the games I’ve played so far, partly because it uses repeated generic screens to add space between important locations. This sparser layout follows from the hybrid nature of the game, since it gives the player some room to run into random monster encounters between puzzles. This makes mapping a bit more challenging, but it’s mostly fine. Though I do want to address the elephant in the room right away…

Boy! Especially after playing Space Quest III, with it’s gorgeous cartoony space environments, this game is hard to look at. Some of the character animations are charming, to be fair. But I was ready to leave grainy pixel color mixing back in the bad old EGA days of my childhood. I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt and assume the blending worked better on a fuzzier CRT monitor, but on a modern machine it is pretty hard to look at. Anyway, not to belabor this point. There are a lot of other things this game does well. Let’s get into one of them.

CHARACTER CREATION

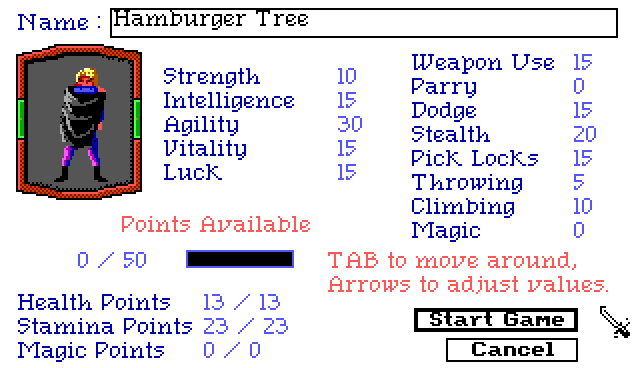

As in any game with a significant amount of roleplaying game in its DNA, you start Quest for Glory by making important decisions about a bunch of stats you barely understand. I could probably learn more about these stats by looking at the manual, but look, I have a formula that works and it doesn’t involve knowing anything about what I’m doing beforehand. And good thing too, because the manual GOG shipped with the game is for the VGA remake, which has a completely different interface for a lot of stuff.

Your first choice is to pick one of three classes: Fighter, Magic User, or Thief. Twitter told me to pick Thief so I did, inadvertently dooming myself to doing everything the hard way forever. You get some starting numbers appropriate to your character class and 50 points to spend on whatever stats or skills you fancy. There’s no real way to know how important any of these are (SPOILERS: THEY’RE ALL INCREDIBLY IMPORTANT), so I took a conservative strategy and added a few points here and there to the stats and skills that were already high.

In theory, you can use this system to make hybrid class builds, like a stealthy fighter or a battlemage. I didn’t mess with this much, which I regret a little. A tiny bit of magic may have helped Hamburger Tree out of a few scrapes. It’s also an impressively flexible system; it would have been reasonable to streamline character creation, given that this game wasn’t aimed at experienced roleplaying game players. Instead, the developers went for something that lets the players tinker a good amount, which is neat (if a little overwhelming at first).

One of the factors contributing to this flexibility is that it’s a use-based skill system. That is, skills increase as you use them, like in Skyrim or Fallen London. (The other common alternative is level-based skill systems, where actions increase a total experience pool.) Use-based skill systems tend to encourage looser character builds because you can’t turn everything you do into experience for your class’s core skills. If I stab, I get better at stabbing, not sneaking.

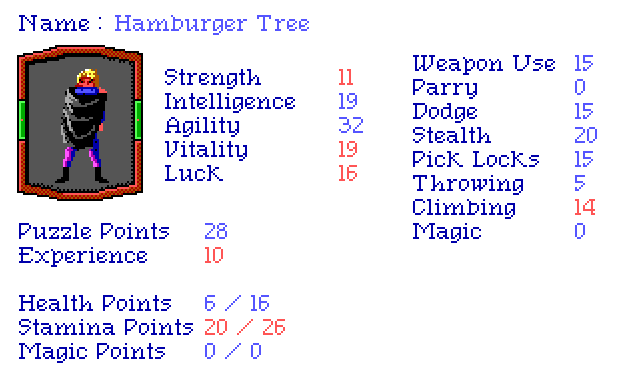

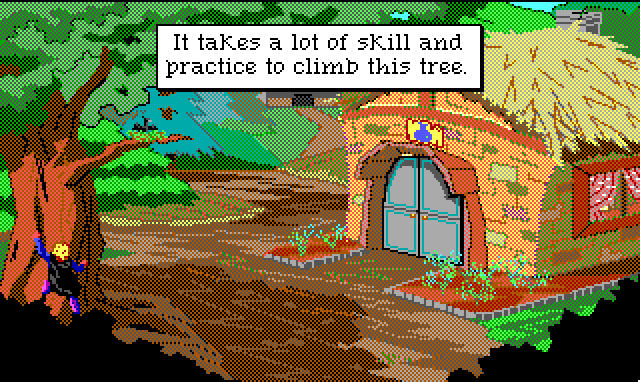

Your actions also increase appropriate stats, which is an interesting twist. So, for example, say I climb a tree unsuccessfully about a hundred fucking times. This increases my Climbing skill, but also related stats such as Strength and Vitality. Increasing Vitality, in turn, affects your max Stamina, which drains as you perform physical actions like fighting or climbing trees. All of these recent changes are marked in red when you open up your character sheet, which is a nice user interface touch. It’s a real feat keeping track of all these changes even with the extra help.

So all of this means that if you’re stuck on anything, well, you can do a bunch of skill grinding to get past it. You also usually have some options about what to grind. And everything you do affects more than one thing on your character sheet, so all the stuff you do to get past puzzles usually improves your base survivability as well. Which is good, because it is a brutal world out there in the wilds of Spielburg.

FIRST QUEST: CAN HAMBURGER TREE SURVIVE THE DAY?

At first, I flailed around for a bit trying to do the quests on the Adventurer’s Guild board. But for most of them I had no idea where to even start. I don’t know where to look for a kidnapped daughter! The only remotely viable option was the blatant tutorial quest: find a ring that the local healer lost. So I did that, which is where I learned to climb a tree so good, and was rewarded with a little money and also the healer grabbed me and kissed me for no reason. Finally, a romance plot?

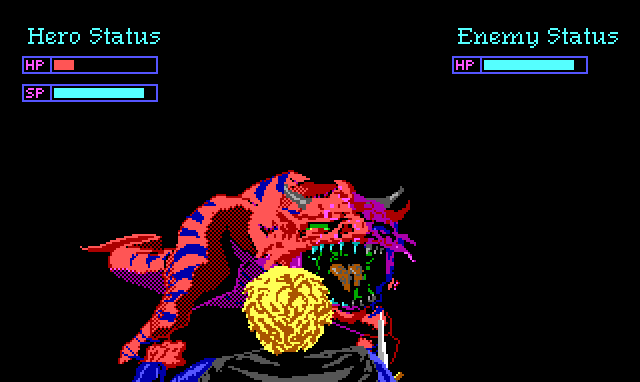

I immediately spent my newfound cash on armor and knives because I know the score in roleplaying world. Gotta get equipped up so you can kill the monsters and get the loot to buy more equipment! Time to go fight some stuff HOLY SHIT

It turns out that the Thief is VERY bad at fighting, gang! Also fighting in this game is PRETTY DIFFICULT! You know that Elder Scrolls thing where you dodge or hit in real time, but it only sometimes works because of stat rolls? Imagine that, but you are made of tissue paper. I tried throwing daggers at things before they attacked me, which was a great way to knock a pixel off their health bar and disarm myself. It became quickly clear that my most valuable combat skill was running away.

I ended up having to do this a lot as I explored the wilds. Enemies can randomly appear in the generic screens as you enter them, and if they touch you a combat starts. You can run away before or during the encounter, but they’ll chase you, and some types of enemies are faster than you. This added a considerable degree of difficulty to my initial effort to map the area. Not only did monsters keep chasing me away from sections I was trying to explore, but since a lot of the screens are repeated, it’s easy to get lost when you’re fleeing for your life.

All this meant that I had seen very little of the world by the time the sun started to set, and also I had spent all my money on new daggers. The day-night cycle is another new element in the game. King’s Quest IV had an internal clock and would eventually switch from day to night, but that was more akin to an act break than the more simulation-flavored version in Quest for Glory. Not only does time progress, but Hamburger Tree also needs to sleep and eat. Failure to do so will damage his stamina recovery (and, I think, it’s possible for him to die of starvation).

The day-night cycle works by moving through a set of discrete stages – morning, midday, evening, early night, etc. – each of which has different lighting and implications for character positions, possible actions, and general level of danger. Bad stuff comes out at night. I assumed as much, since I have ever played a game before, and so as soon as evening set in I went running back to town, thinking I could get a room at the inn. Imagine my distress, then, when I found the city gate closed. In desperation, I went back to the healer who seemed so handsy earlier, but no luck there either.

This was a problem. Not only was I broke, out of daggers, and clearly unprepared for anything around me, but by this point my stamina was totally run down. I made a half-hearted attempt to climb the city wall, but I was too weak to do the grinding necessary. At this point, primed by previous Sierra games, I assumed I had already lost the game and would have to return to a previous save (or just restart). (Maybe as a less flimsy class.)

But I had one last idea left: besides the healer, the only other person in the game who had been nice to me so far was a dryad who gave me a quest way off in another corner of the map. So I gathered what little stamina I had left and ran the entire way, getting lost only a couple times, while various dinosaur things and giant panthers swarmed me every other screen. Against all odds, I made it. And even more unlikely, it turned out that this was a safe place to sleep.

Delightfully, the “Hamburger Tree is sleeping” sprite is identical to the “Hamburger Tree is dead” sprite, which caused me a little worry at first. But no, I made it through the night, and woke up with my stamina refreshed. But not, to my distress, my health points. The only way to recover those is with health potions, which cost money, which I did not have. So I began my second day, wondering how I was going to solve all these adventure puzzles while also traversing a hellscape that wanted me dead at every turn.

DAILY LIFE

Hamburger Tree, with the aid of saving and loading, survived the second day, and the third, and the fourth. Indeed, he settled into a routine of sorts. Along the way, I grew fond of how this goal of surviving day to day bumped up against the quest to find objects and apply them to problems.

In the early days, Hamburger Tree had two problems: 1) no idea how to further the main plot and 2) a complete lack of resources necessary for survival. Based on earlier games, my best plan to deal with problem #1 was to walk around and map the whole area, discovering all the rooms with puzzles in them so I could then look for stuff to solve them with. I pursued this goal over about the first week of in-game time.

For the reasons mentioned earlier, this was something of a slow process. Quest for Glory certainly found a way to make this exploration phase more exciting. Despite my best efforts to run away, I kept getting hurt, and also occasionally lost my daggers in foolish attempts to throw them at monsters. Thus, problem #2: I needed lots of health potions and daggers. Which means I needed a source of income.

I took stock of my options as I understood them. I could probably get money from killing monsters, but the idea that I would ever kill anything seemed nonsensical. I was supposedly a thief, but most of the locked doors in town didn’t lead anywhere, except for one which led to me getting eaten by a cat. I ended up with two options that seemed Hamburger Tree’s speed: mucking the Baron’s stables and, most lucratively, collecting mushrooms for the healer.

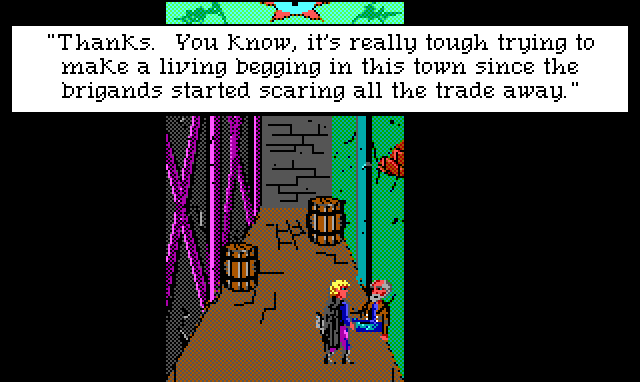

The magic mushrooms were just sitting around in a forest location, and she gives you a whole gold piece every day if you bring her some. A steady income! By cobbling together the money I earned, I was able to keep myself in enough potions to explore the whole map and get a better idea of where things were. I slept under the dryad tree every night and managed to keep my injuries to a minimum. My extremely modest success made me generous, and I befriended a local beggar by sharing some coins with him. This doesn’t do anything, but we had a nice chat.

Little details like this are a nice touch. There are a lot of characters and things you can interact with that don’t have anything to do with puzzles, or which you can skip depending on your class and play style. Unlike games in the other Quest series so far, there’s a sense here that your quest isn’t the only thing happening in this universe. Characters move around doing their jobs instead of standing around, representing a puzzle. I dig it; I like that the world doesn’t feel like it’s waiting for you.

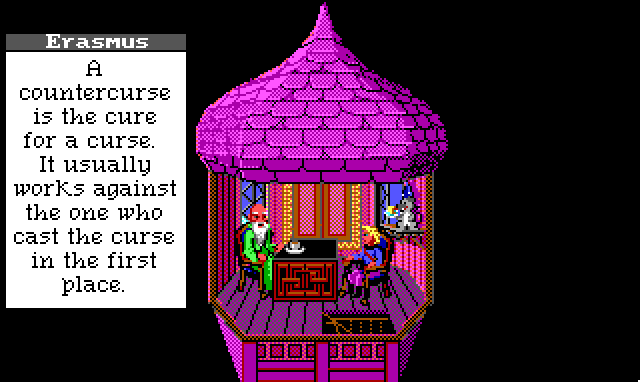

In my travels, I also became acquainted with a couple of wizards. One lived in a cave by a waterfall and the other lived in a fancy tower, but both shared the remarkable quality of having literally any useful information about the main quest.

Both of these guys immediately start gossiping about all the other magic users in the area, which is delightful to me. None of the normal villagers ever really talk about the wizards, and the wizards only talk about each other, implying that there’s a. insular magic community in this region. Kind of a town-and-gown situation. They both gave me hints about how to deal with the bandits’ wizard, while Fancy Tower Wizard Erasmus gave me a whole monologue about the real story behind all the recent troubles. Turns out the great Baba Yaga had cursed the baron, probably because he deserved it, which resulted in various bad things happening to his kids.

This seemed important to the main plot, but also not something I was equipped to deal with at the time. I continued to bide my time, figuring I could improve my skills gradually to the point that I could actually fight something and start doing plot-relevant things. I identified some likely locations of quests, all gated by ominous stuff: there’s an interesting cave up north with a giant troll in front of it, a chicken-legged house to the west that presumably marks the location of Baba Yaga, and, down south, the bandit stronghold surrounded by spikey-looking dudes.

All of these places seemed considerably too dangerous for my capabilities, but I imagined that someday I would build up enough skills to sneak past the troll or the bandit guards. I had a life plan in place. Things were looking up for Hamburger Tree!

But then, my world turned upside down.

Can Hamburger Tree survive in this new economy?? Will he ever quest for anything, much less glory?? Tune in next time, as our hero does crimes, gets famous, and learns a valuable lesson about multitasking.