Line on Sierra: Space Quest III

September 19, 2016 - Features / Line On Sierra

Welcome back! The ongoing Police Quest problem notwithstanding, at this point we are firmly within the Golden Age of the text-based Sierra games, and I am prepared to get pretty gushy about Space Quest III: The Pirates of Pestulon.

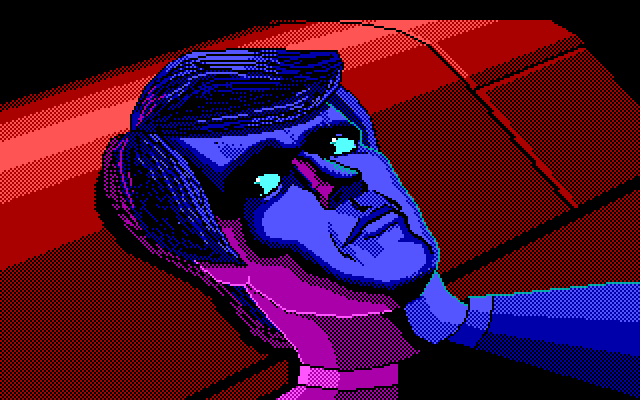

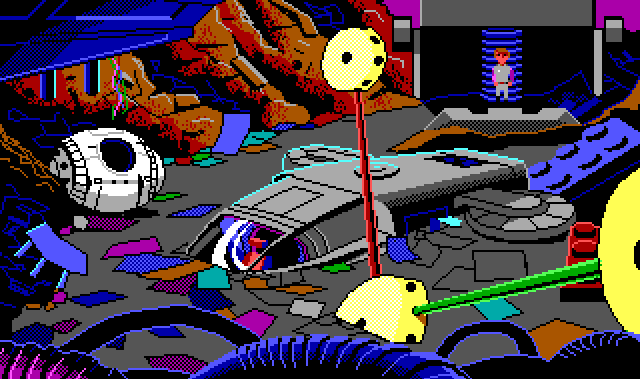

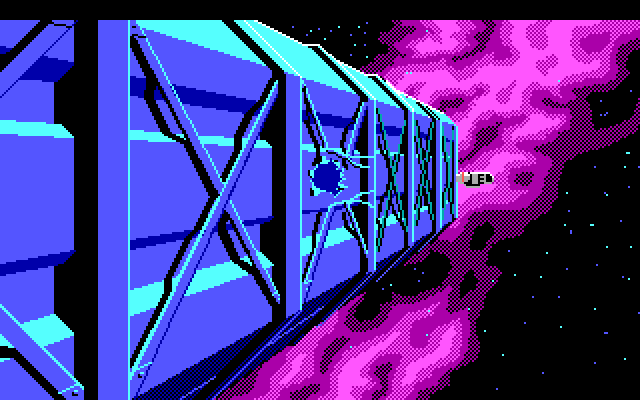

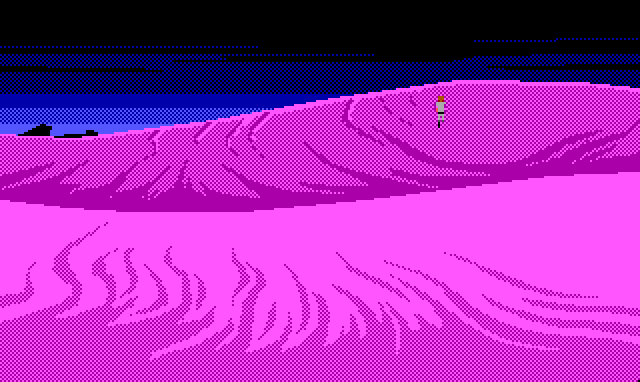

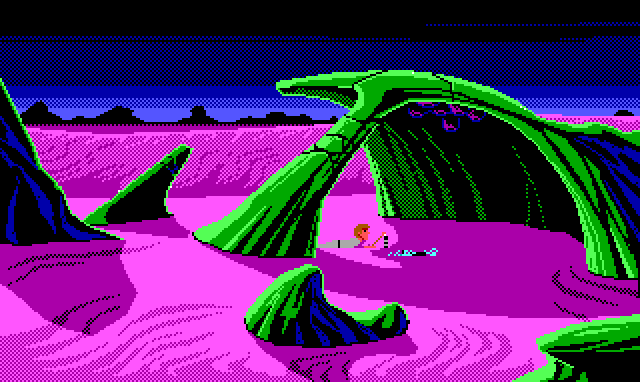

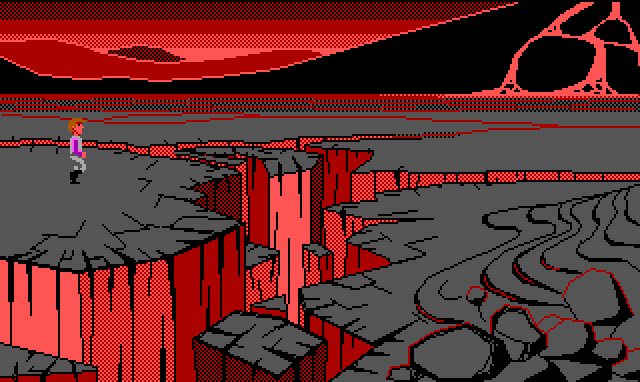

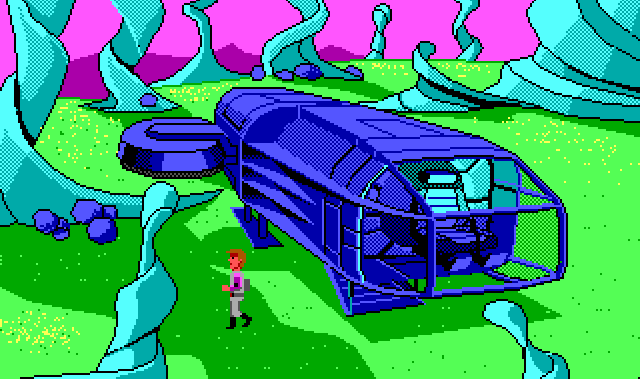

One thing about this game is obvious almost right away: compared to previous Sierra games, it looks fantastic. Space Quest III uses the same engine as King’s Quest IV and Police Quest II, Sierra’s Creative Interpreter 0, but the visual design is much more focused and purposeful. A common theme so far is that Space Quest in general has a clearer tone and point of view than the other two series, and in this installment that extends to the visual style as well. Mark Crowe, who along with Scott Murphy makes up developer team Two Guys from Andromeda, is credited with the graphics.

Although Space Quest III uses the same 16 colors as every other game on the engine, it spaces those colors out between scenes and locations to make different areas feel distinct. Shots often have one or two dominant colors with a couple of accents; by contrast, both King’s Quest IV and Police Quest II have a certain comic-booky flatness that comes from using whatever’s at hand from a limited color range all at once. It’s a smart way to turn a technical limitation into a creative strength.

Space Quest III starts with protagonist Roger Wilco waking up in the sleeping pod he dramatically reached at the very end of Space Quest II. An indeterminate amount of time has passed, and he’s been picked up by a garbage freighter. This transformation of janitor into trash is, of course, deeply symbolic and important.

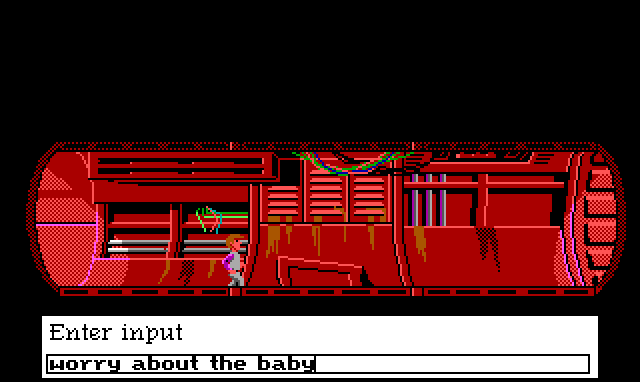

Now, listen. Loyal fans of Line on Sierra may remember that Roger was nanoseconds away from giving birth to a chestburster when he jumped in his sleeping pod at the end of the last game. Shockingly, the sequel completely ignores this fact, like my choices don’t even matter. How disappointingly linear, Two Guys.

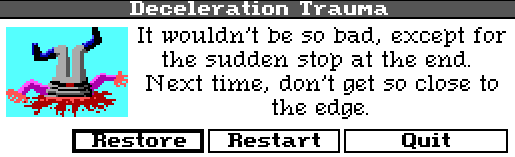

The garbage freighter is the first and largest of several environments in the game that lend themselves to a bit of exploration and item collection in the King’s Quest style. Because it’s a Space Quest game, there are lots of outlandish and comical ways to die while you do this, although I do like to stick to the classics.

If there’s one thing I can say confidently about this series, it’s that I’ll never learn anything about how not to fall from great heights.

As I explored the garbage freighter, I started to turn around a certain conundrum in my mind, one which will surely hang over future installments of this series. While I still keep a walkthrough handy to keep myself from getting completely stuck, I found it much easier to navigate the puzzles in this game, as I did to some extent in King’s Quest IV. Which raises the question: is this because Sierra’s puzzle design was getting gradually better as the genre matured, or because I’m subconsciously remembering solutions I played through as a child? I suspect there may be elements of both, which is going to make it a bit tricky for me to talk about the evolution of the puzzle design in these games.

That said, my memory is selective, so the things that are easy are probably going to reflect what interested me as a kid. I’m pretty sure I remembered, for example, that I needed to climb up to the top and use some kind of claw game to move parts into the ship I found. Playing with the claw was fun! But a whole series of shenanigans with a space rat that steals your stuff and hides it left me backtracking and digging through the walkthrough as much as anything from Police Quest.

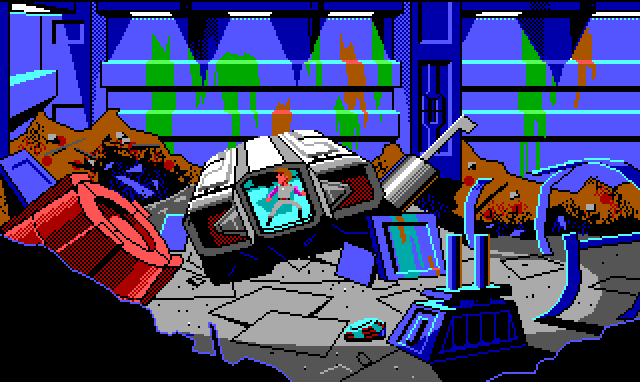

Not to get too far ahead of myself, though. The big point of the garbage freighter is that you find the aforementioned ship, which like all scifi comedy spaceships is named after some variation on “Millennium Falcon” that I forgot as soon as I heard it. This first location fits the pattern of previous Space Quest games, in that all the puzzles in the area are built around the goal of escaping it. In this case, you have to find various spare parts to fix up the ship so you can get it started.

After you’re done with that, Roger finally has a crappy little spaceship, like a real scifi videogame hero! I included this particular shot because I’m pretty sure it’s the one that I vividly remember blowing my mind as a kid with its advanced graphics. “I guess this is what videogames are going to look like in the future,” I thought to myself, with a fascinating edge of regret for the waning days of noodle-legged sprites. Roger does kind of look like a really nerdy Doomguy here, I guess, if my prediction was off in various other important ways. It’s good to know I was weirdly specifically fatalist from such a precocious age, though. Don’t worry, 8 year old Line! The noodle legs will return in time, and they’ll bring a lot of symbolic platforming with them.

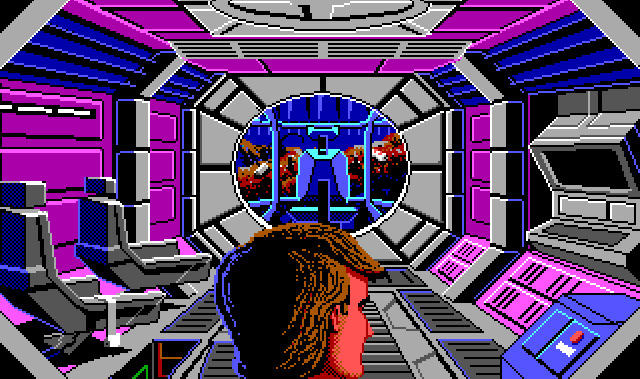

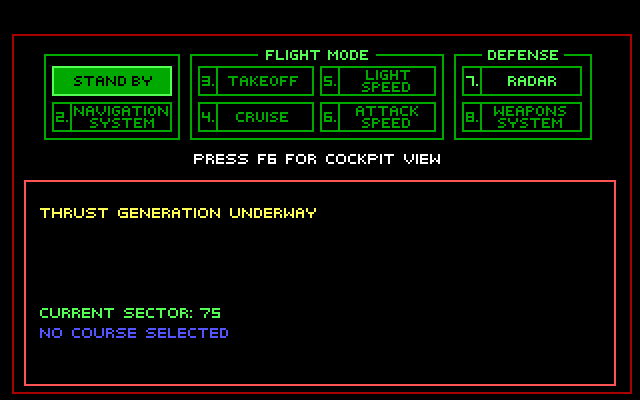

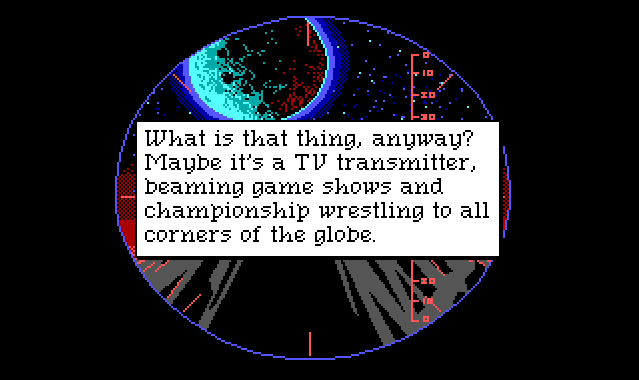

Once I got the ship working I was treated to this screen, which immediately filled me with despair. I always suspected the Space Quest designers were just waiting for a chance to break out a fuckin flight sim! Fortunately, my fears were mostly unjustified. Starting up the spaceship is a matter of hitting the right keys in order, and there’s no sudden death punishment for getting the order wrong.

The one exception is the battle system, about which more later. At this point all you have to do with it is put shields up in front and then blast your way out of the freighter (in another fantastic shot). But! this is really interesting! Because that is a low-stakes tutorial, built into the storyline, that shows you how to do something you’ll be doing under pressure much later in the game. Now, it’s hard to remember the last time I played a long game that didn’t do something similar. For example, the most recent game I played, Style Savvy: Fashion Forward, starts with a character seeing a hat and begging to try it on so I can learn the dress-up interface.

But while that may be game design 101 in 2016, it’s an entirely new thing for a Sierra adventure game, if not any kind of game, in 1989. Police Quest II had the shooting range, which a player could use to practice the keys needed for shootouts later in the game, but the first person view of the shooting range is not a direct (or effective) tutorial for shooting a moving sprite in a third-person view. This is a case where you’re doing the exact same actions you’ll be doing later, and where it’s presented as just another puzzle you need to solve to progress the story. This is shockingly modern game design!

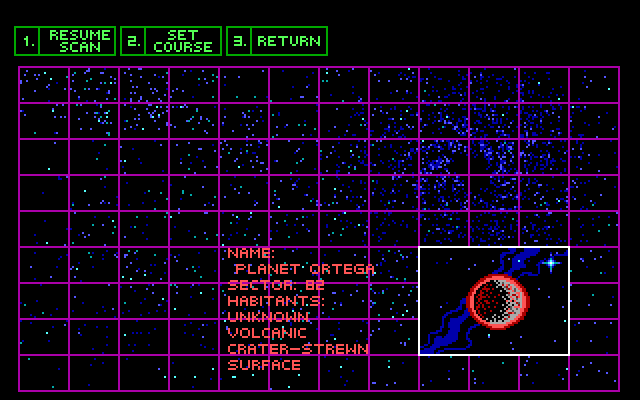

Another modern twist immediately follows. Once you get the ship operational, you can then open up the navigation interface and scan for planets. This reveals three locations to select from. This immediately recalls the “visit three areas in any order, then unlock a plot-advancing area” structure familiar to players of Bioware epics and other semi-linear narrative games. Space Quest III just can’t stop inventing the future of videogames. This technique is still popular because it’s a low-cost way to give the player a sense of free exploration without turning your narrative structure into a big tangled mess. It makes a lot of sense for Space Quest, which used an episodic structure from the start.

That said, the choice of three planets is a bit of an illusion: you can’t immediately go to the fire planet Ortega, since you need an item from another location to survive the heat. From a remove, the structure is not far off from King’s Quest IV: get three items which each unlock the next phase of the plot, then trigger an endgame. To start with, you can either go to the planet Phleebhut or, like me, head straight for the Monolith Burger. Roger’s been in stasis for god knows how long! Dude’s gotta eat!

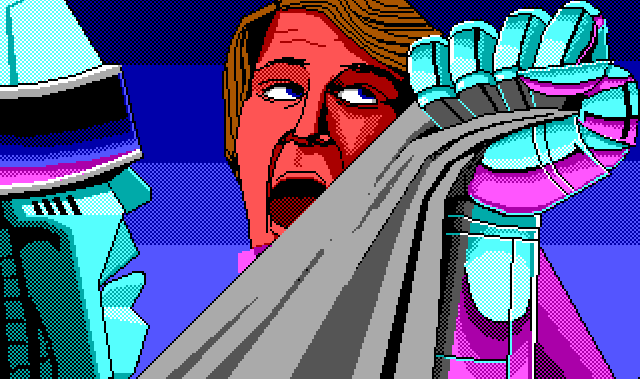

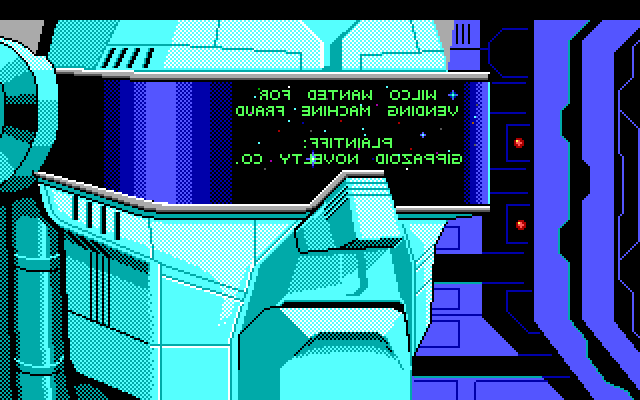

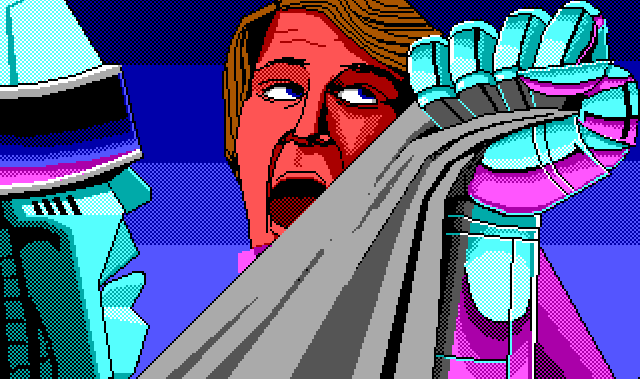

Before we get there, there’s another quick glimpse of the cinematic storytelling style I’m starting to associate with the series. Navigating anywhere triggers a cutscene in which a large Terminator-style robot gets mad at Roger. The backstory explaining this shows up in reverse on the robot’s visor, which is a weird and striking way to dump exposition, if one that might raise accessibility issues. The robot’s quest to destroy Roger over petty theft is unrelated to the main plot of the game, but turns out to be a useful way of gating some of the plot down the line.

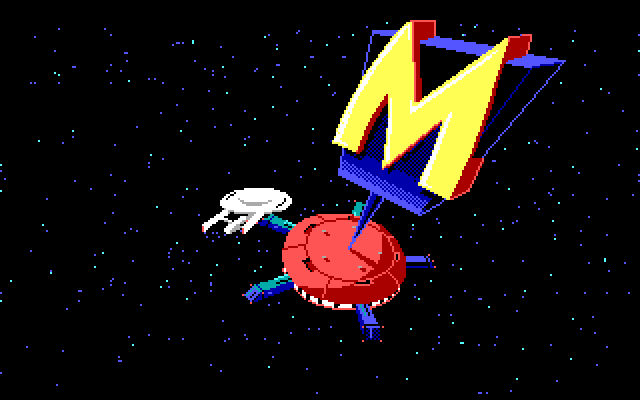

The establishing shot of the Monolith Burger is great, and also the strongest evidence yet of how much Space Quest DNA lived on in Futurama. I was drawn to this location not only because it seemed like the wrong place to go first, but also because it exerted a powerful pull of nostalgia on me. Indeed, this image of a weird little rest stop floating lonely in the middle of space would live in the back of my mind for years. My final project in my undergrad graphics course would come out looking quite a lot like a Monolith Burger.

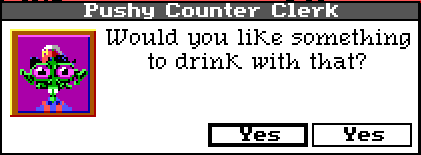

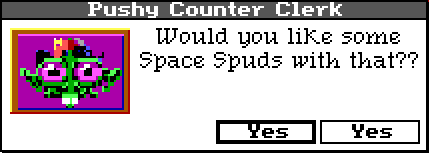

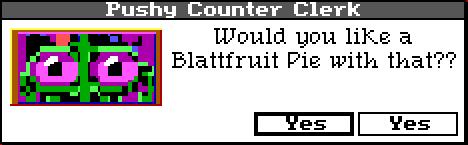

Maybe because of how it implanted itself on my memory, I found myself knowing exactly what I was supposed to do in this scene: walk up to the counter and order a kid’s meal, because the prize was something important. This triggered a little sequence which made me laugh probably as much as it did when I was eight.

I love how the dialogue boxes themselves expand in size to fit the increasing zoom levels. It’s such a nice touch.

I was right about the kid’s meal prize. It was a secret decoder ring that I had no immediate use for, but seemed important enough. I hung around the Monolith Burger a bit longer getting in fights with aliens, but I knew in my unsettling memory banks that what I needed to do here next was play the arcade game in the restaurant about a billion times, which meant I needed a lot more money. So: on to planet Phleebhut!

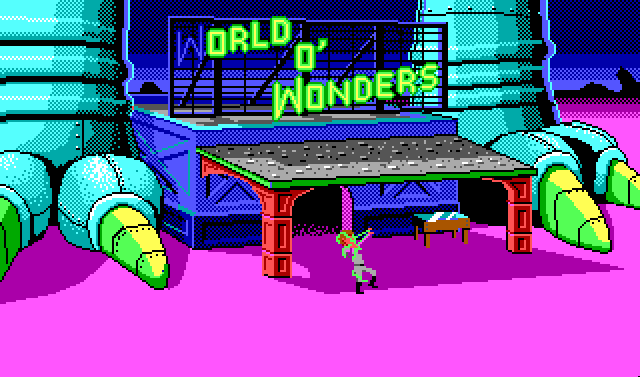

Phleebhut (which is a bad name and I hate typing it) is another space set up for a bit of exploration. It’s still a small area by King’s Quest standards, but it’s big enough that a bit of mapping is necessary, especially since I’ll be racing through it on a time limit later. Most of it is empty, just big purple dunes and smooth green rock formations. The only point of interest is a giant dinosaur-shaped tourist attraction at the top of the map, where the main action of this segment will take place.

(This screenshot depicts Roger dying gruesomely for no good reason, in case you forgot that this is happening constantly in between all the rest of the action.)

This is an unusual use of space for a Sierra adventure game, and it’s pretty cool. The planet could have been designed such that you land your ship right next to the dinosaur. Instead, you wander around a desolate space for a few screens, see either a signpost or the dinosaur in the distance, then arrive at a place that immediately seems noisy and colorful by contrast. There’s a narrative build to it that makes the joke land better. This sequence, more than any other, gives the impression that Roger’s journey in this game is more or less just a road trip across the American Southwest.

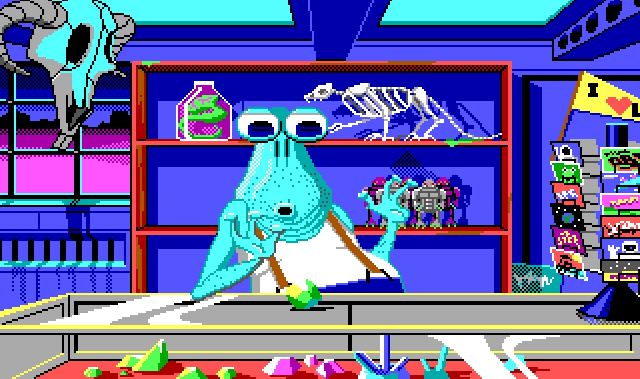

Inside the dinosaur is a kitsch shop run by an alien with high-quality facial expressions. He sells various things that sound useful, particularly the thermal underwear that will allow Roger to survive Ortega, as well as a collection of postcards containing references to other Sierra games and beloved science fiction franchises. I was troubled that my quest for money had only found me more things to buy. I had to hit the walkthrough to figure out that I was supposed to sell a gem in my inventory that was left over from the previous game. Nice continuity, but WHERE’S MY BABY, TWO GUYS?

This gave me more than enough money to buy everything in the store and have enough left over for arcade game shenanigans. But as I was leaving, plot twist! The robot shows up!

The robot gives Roger a head start to get away, which kicks off a fun chase sequence. The robot turns invisible when chasing Roger, so when he shows up in a screen it’s just as some ominous footprints behind you. This is both a neat effect and probably a good way to avoid multiple animated objects on screen while the player is doing something time-sensitive.

A cool thing about this sequence is that you can solve the puzzle in two different ways. As one method, you can lead the terminator bot into the upper levels of the dinosaur and knock him down. I went for the second method, which is to lure him under some alien fungus things that ate me several times while I was exploring the planet earlier. I found this very satisfying. Both puzzle solutions are very environment-driven, and depend on the player having sufficiently explored the space prior to triggering the chase. This is one of those cases where I’m not sure whether I subconsciously remembered the solution or the puzzle was just well-designed, but I’m inclined towards the latter. There’s something clever about prompting the player to think about hazards they encountered as something they can turn against an enemy.

Once the robot is taken care of, you can snag its invisibility belt and get the hell off of Phleebhut. Now that I had infinite money, I knew it was time to head back to Monolith Burger and die a billion times in the fucking chicken game.

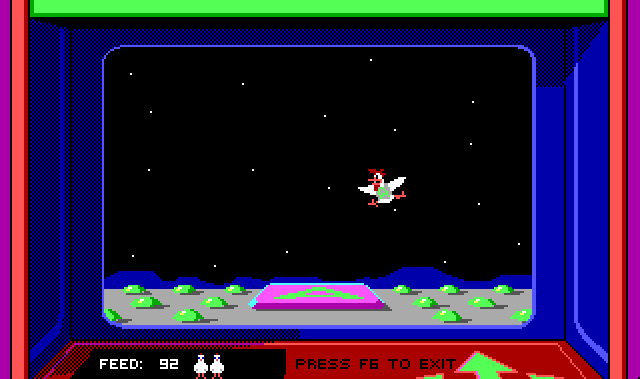

The chicken game! Classic Sierra adventures inspire strong feelings in those who grew up with them: affection for their environments, weird puzzles, and storylines, and pure seething hatred for their minigames. Astro Chicken, a take on Lunar Lander with awful controls and a chirpy soundtrack, is among the most loathed of these. Death is frequent, largely unavoidable, and accompanied by impressively annoying sound design.

To be fair, in the context of the game’s storyline, I think that Astro Chicken is a genuine attempt to come up with the worst possible videogame. After you play it enough times, you unlock a secret message from the game’s developers, which you can translate with the decoder ring from the kid’s meal. It turns out that the Two Guys from Andromeda are being held captive and forced to develop games on Pestulon, a moon of Ortega. Way to break the fourth wall, Two Guys! Which means there’s a sort of low-key joke that Roger (and by extension, the player) is the only person who could ever stand to play Astro Chicken long enough to get the message.

There’s a lot that’s interesting to me about the storytelling in Space Quest III, not least that they wait until about two-thirds of the way through the game to tell you what the plot is. It turns out that there’s a good reason Ortega was locked until you got through Phleebhut: once you get there, you advance the plot to the final sequence. But here’s something I find even more interesting. The Monolith Burger scene is, technically, totally optional. Getting the secret message tells you what the plot is, and gives you an idea of what you need to do on Ortega, but you can skip it and go straight through if you want. Amusingly, if you do that, the game text reflects that Roger has no idea what he’s doing on Ortega or why.

Well, what you’re doing is blowing up a shield generator that prevents you from landing on Pestulon, the moon where the Two Guys are held captive. Once you do that, it shows up in your navigation scans, and the final act can get started.

Pestulon’s weird spiral fungus-trees are another great design.

It’s at this point that a lot of the narrative gating in the game becomes apparent. Since you had to go to Phleebhut before Ortega, and you absolutely had to kill the robot to get off the planet, that makes it very likely that the player got the invisibility belt right before they left for Ortega. In between, they can optionally stop by Monolith Burger to get information about the plot. The invisibility belt is then necessary to get past the guards on Pestulon. So despite the open-space implications of the opening, there’s an ideal path through the three locations that the player is kind of fluidly guided down by the need to get certain items to get past obstacles. There are definitely possible snags: the player may not see the belt in the robot’s remains, they may (like me) not figure out how to get money, etc. But overall, it’s a pretty nice take on making King’s Quest II‘s hyper-literal “get three keys, open three doors” into a more organic narrative structure.

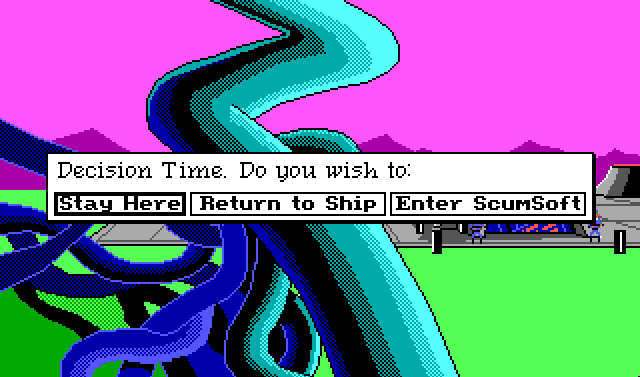

And then for some reason, once you get to the building you need to enter, you get a false choice dialogue. This is so silly! If you stay or return to the ship, nothing happens. I think this might be an attempt to make Roger’s infiltration of the base feel more momentous, and I can see where this might work. But I don’t think it’s a great move in an adventure game, where odds are high that Roger will die comically thirty seconds after making his dramatic decision to push forward.

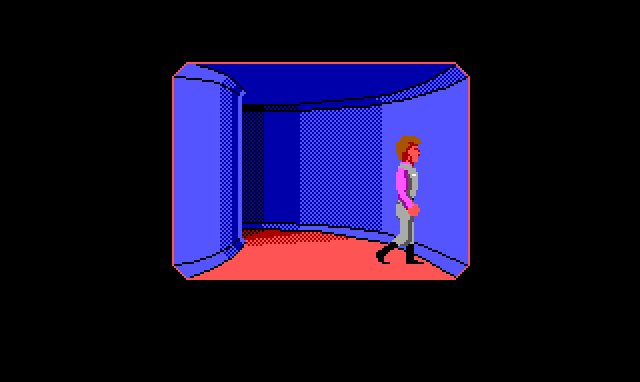

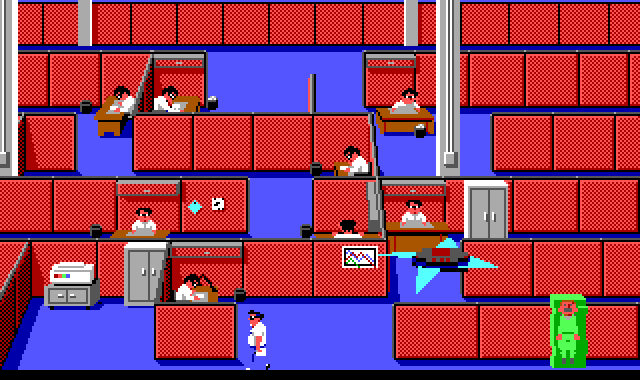

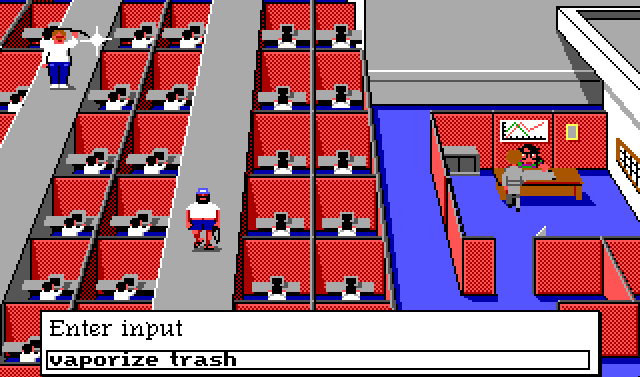

Or just walk into a wall repeatedly. Once you get inside the base, you’re treated to an interesting and terrible new movement scheme, which sees Roger walking around a donut-shaped hallway and trying to enter doors that are, like, pretty small targets from this camera angle. One is locked by a keycard, which marks it as important, and another is a massive cubicle maze where you get comically killed if you wander into it right away.

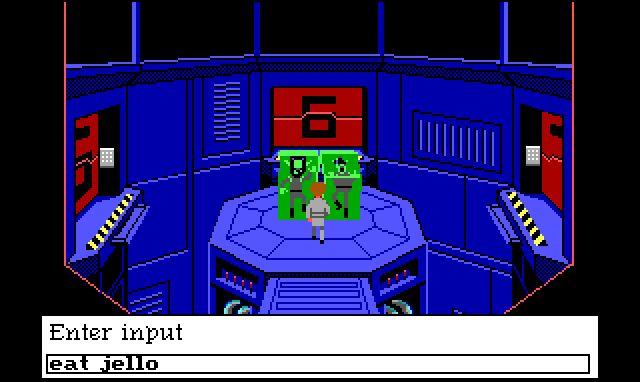

The last, however, is a janitor’s closet, where Roger can symbolically shed his space adventurer trappings and put on a janitor’s uniform once more. This disguise lets him navigate the cubicle maze, but only if he diligently empties every wastebasket he passes with his new trash vaporizer. Errors will get you noticed and subsequently zapped by a drone, which encases you in a large block of Jell-O. I’m not sure what the point of all the Jell-O encasing is, but it’s definitely a thing. This seems like the kind of attack that would be used to make a game technically nonviolent for family-friendliness, but this is Space Quest, and every other death in the game is rewarded with a closeup of Roger tied up in a knot and bleeding out his eyeballs or something.

Like so. I guess the green Jell-O just adds a little variety to all the red.

Roger’s stealth mission eventually leads him to the director’s office and a little visualization of game development crunch circa 1989. The Two Guys had some shit they were working out with this game! Here you can steal the director’s keycard and finally break into the secret room. You can also go out on a balcony and see your ship parked next to the building, but you can’t reach it at this point. This is an interesting bit of foreshadowing that will help explain how you get there later. It’s another small way that this game makes the space it takes place in a little more cohesive.

When you get to the secret room, you find the Two Guys, who are, naturally, encased in Jell-O. You can use your trash vaporizer to free them (sadly the more win-win solution I proposed was not accepted), at which point the ramp retracts and the developers ask Roger what his plan was to escape. Meta! The first time through, I immediately panicked and jumped off the edge. This was not correct. It turns out it’s just an inescapable sequence where the director re-captures you and the Two Guys together. There’s a cute background joke where your score rockets up to the full amount after you free the Two Guys, then plummets back down when you get captured again. This is fitting, given all the fourth wall shenanigans going on, and a neat way to tease the false ending for all the nerds watching their score.

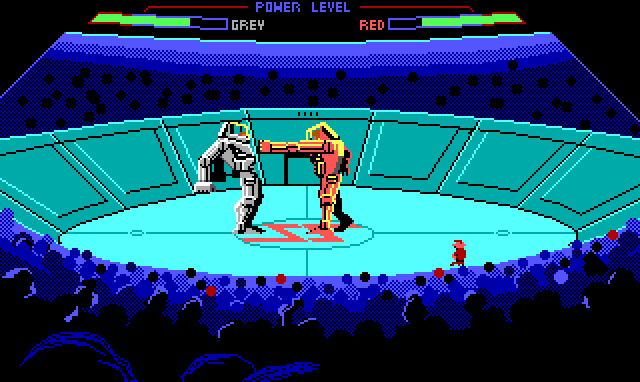

After the director captures you, he subjects you to robot combat for reasons that are unclear to me in retrospect. But you know, someone wanted to get their climactic robot fight in, and that’s fine. That’s fine.

I’ll tell you this: for all the hate Astro Chicken gets, it’s just a goofy sequence that you can fail your way through without consequence. This robot fighting minigame, done in a Rock-em Sock-em Robots style, is the one that made me truly miserable. The controls are just as janky as Astro Chicken, but slower, without narrative justification, and in a life or death situation. I HATE IT. As is becoming my go-to strategy for life-ruining Sierra minigames, I started cranking the game speed up and down in search of a sweet spot where it didn’t make me cry and kick furniture. I finally managed to beat the fight in ultra-slow-motion, like it was some kind of terrible turn-based fighting game.

After you win the fight and escape, the space battle tutorial from the beginning finally pays off. You have to shoot down several ships sent after you by the software company, which involves switching around your shields as they approach then chasing them with a cursor until you lock on. It’s finicky and ends in death frequently, but surprisingly I found it pretty fun. That’s the power of an organic tutorial!

After the space battle, there’s a momentary peace in which the Two Guys yammer at Roger for a bit. But then the ship gets sucked into a wormhole… one which lands them all near a mysterious planet on the other side of the galaxy….

The meta shenanigans continue! And what’s this?

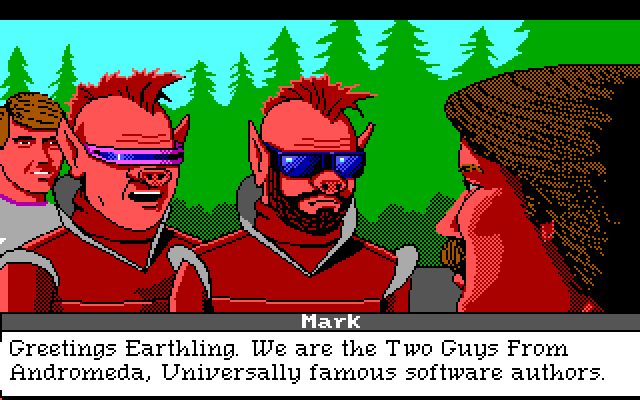

Look at these fuckin nerds, writing themselves into their nerd-ass space game. I love everything about this whole situation, from the Two Guys’ lovingly rendered Spacepigsonas, to Ken Williams’s pixel mustache, to Roger looking like a photobomber in his own videogame. I also love the now-archaic phrase “software authors.” When did that go out of fashion? (Very quickly, according to Google Ngram Viewer.) And finally, the implication that these guys loved Roger Wilco so much they went on to make a series of games about him, set in their long-lost space home.

And then: Kickstarter!

This whole ending is amazingly self-indulgent, but you know what? These guys earned it. Space Quest III actually feels like it learned lessons from all the games that came before it. Puzzles are tied into the storyline better, there’s variety in the stuff you do and the places you go without feeling random, the jokes are pretty funny and the graphics are great. If you wanted to try one game from this era to get a feel for what Sierra was about, this is the one I’d recommend.

Next time on Line on Sierra: GUESS WHAT NERDS, you can finally stop asking me when I’m doing Quest for Glory!

THINGS THAT KILLED ME IN SPACE QUEST III: THE POWER RANKING

Robot fight: 17 times

Fell from a great height: 10

Eaten by space fungus: 5

Terminated: 5

Encased in Jell-O: 5

Blown up by enemy ships: 2

Blown up by myself: 2

Picking up everything, as I have been taught: 2

Scorpazoid: 1

Lightning: 1

Antagonized a dude at a fast food restaurant: 1