Dragon Age 2: The Champion of Kirkwall

August 20, 2011 - Features

It took me a long time, but I finally finished my first playthrough of Dragon Age 2. This is the first of a couple posts I’ll be writing on it. To get the overall opinion stuff out of the way first, I was pretty crazy about the game. I wasn’t too offended by the reused environments, and I found the storytelling changes generally interesting and worthwhile. And damn, it was just fun. Hot boys, engaging backstories, messy skill trees, political shitstorms: all that good Bioware stuff. And on top of that, some clever approaches to character development and story pacing, which I’ll talk more about (with spoilers) after the jump.

The character development – in the roleplaying sense – was really a standout, and I’ve been trying to figure out why, exactly. The main reason I play this kind of game is because I like inventing characters, and I like figuring out who they are by throwing them against an interesting story space. This isn’t always easy. I have two big problems: one, that most of my roleplaying characters end up being pretty much the same, and two, that they always end up being huge goody-two-shoes.

This doesn’t happen because I’ve got some Platonic ideal of a roleplaying character (or myself) that I just inevitably tend to emulate. It happens because games encourage certain kinds of characters for certain styles of play. See, I want to see as much of a game world as possible. That’s my thing, I’m an explorer. So in an RPG, I generally find myself playing someone who supports that play style. So she’s extroverted (gotta see all the dialogue), altruistic (gotta take on every quest), promiscuous (gotta explore all the romance options), etc. On top of that, she’s usually a saint because “good” decisions have a tendency to leave more options open than “bad” ones. You can be all evil by killing off the Rachni Queen in Mass Effect, but that takes a possibility out of the game world, so I can’t bring myself to do it. Same thing with blowing up Megaton in Fallout 3 (seriously? taking a town out of an RPG with like three towns?) or killing Little Sisters in Bioshock. Being good usually means having more stuff at the end. It’s a sweet statement of morality, but it makes it hard to be a morally ambiguous character without feeling like a chump.

Dragon Age: Origins tried to get around this by having a lot of decisions with no good options and a morality system based on character approval rather than some absolute scale. This was great, but it didn’t help me with my problem: I still had my standard chatty, fickle, goody-two-shoes character, only now she was obsessed with making people like her. Didn’t do wonders for her personality.

Looking back on Dragon Age 2, on the other hand, I realized that for the first time I had successfully made an reserved, dismissive, self-serving character who ended up with a lot of bad outcomes. And I didn’t even put much effort into it. This was a great victory for me, odd as it may sound! For once, I didn’t feel pressured into being everyone’s best friend or saving kittens or anything. It was just as easy to be Mallory Hawke, the cunning wiseass who’ll do whatever it takes to preserve herself and her (quietly resented) family. Nice.

There are a few gameplay changes that made this possible, and interestingly, none of them are particularly drastic. One is the replacement of DA:O‘s one-dimensional approval meter for each member of your party with a bipolar friendship/rivalry meter. Back in DA:O, you got stat bonuses if a character loved you, and risked losing them from the party if they hated you. Now you get stat bonuses if a character either loves you or hates you. It’s a simple change that rewards you for having a strong personality, rather than an ingratiating one. In DA2, I enjoyed cultivating my rivalries along with my friendships, and facing one of those enemies on the field of battle at the end felt satisfying and earned.

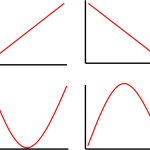

The other slight change was to the handling of the conversation options. Like Mass Effect, this game has a dialogue wheel rather than a list of options, which is a fine cosmetic change. Also like in Mass Effect, the dialogue wheel is roughly separated into “nice,” “neutral,” and “mean” responses on the right side, as an aid in defining your character. Unlike in Mass Effect, these responses are further subdivided into six tones, which appear to be: helpful, peaceful, jokey, pragmatic, aggressive, and judgmental. Right off the bat, this gives you a broader palette to work with. The dominant tones you use also seem to affect your conversation options as you go along, include the persuade options you get. But this is kept much less transparent than in Mass Effect‘s Renegade/Paragon system. This makes character definition feel more organic, but still meaningful. It’s an elegant design.

There are other things I was impressed with in Dragon Age 2, but I’ll save those for a later post. I’m interested to see where the franchise goes from here, based on the stylistic choices the designers have made so far. They seem to be deeply concerned with questions about how to maintain narrative tension in a game world and how to build a story around an uncertain protagonist. They don’t always hit the mark, but I’m glad as hell someone’s trying.