This Is How We Forget History

January 5, 2015 - Features

I’m usually patient with new TV shows. I’m a Fringe fan, after all: sometimes it takes a few episodes or seasons for a show to find its legs. So like, I was skeptical about AMC’s Halt and Catch Fire, but willing to give it a chance. It’s set in 1983 and about the growth of personal computing. Early reviews were a bit rough, but like I say, I’m patient. I like computing history!

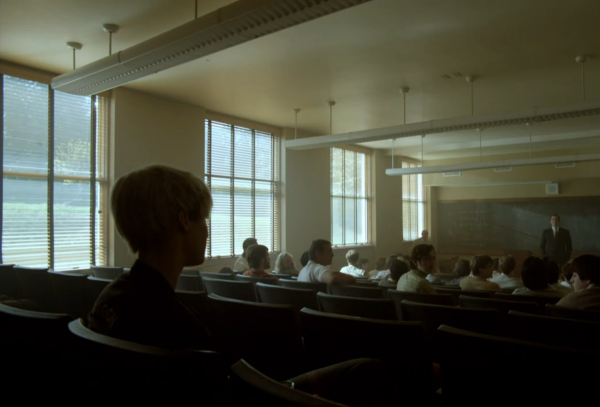

In this case, though, the show lost me in a single scene, before the credits even rolled. Two shots, really. It’s this one:

And this one:

This is a scene that introduces two of the main characters, Joe McMillan (the suit) and Cameron Howe (the woman). Joe is a Xerox of a Xerox of Don Draper; Cameron is the Cool Hacker Girl. Not thrilling, but acceptable on paper. But the visual rhetoric in that shot of the classroom where Joe and Cameron meet got me anxious about where things were going. I made it through one more episode to check my instincts, then bailed. From what I’ve read, I might have liked some of the places the series went if I’d stuck around. It just happened to hit me in a place I was already too sore.

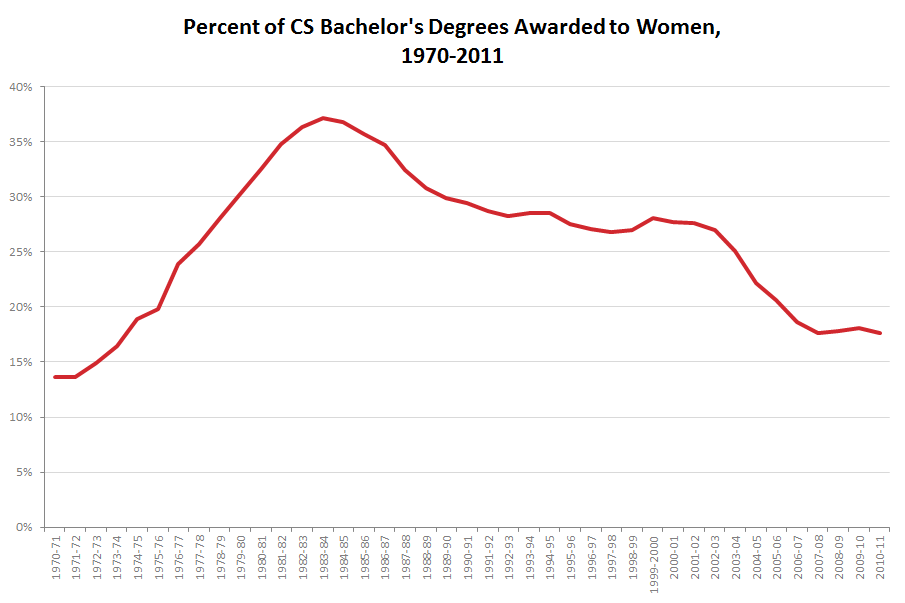

The thing is, that all-male class is a glaring historical inaccuracy. Halt and Catch Fire‘s first season is set in 1983, a year in which the proportion of undergraduate computer science degrees awarded to women in the United States had just about reached its historical peak. To portray a typical computer science classroom of the period, over a third of the students should have been women. If this is surprising to the writers or viewers of the show, it’s because of fictions we tell ourselves as a culture, fictions that are embodied in the Cool Hacker Girl archetype and how it gets used.

It’s possible that the writers just didn’t know they were making an error. They might have looked at the low rate of women in computer science programs in 2014, and made the enlightened liberal assumption that things have gotten better. There must have been even fewer women in computing thirty years ago! But in this case, things haven’t gotten better. The proportion of computer science degrees award to women has plummeted since 1984, even as the number of those degrees granted has skyrocketed.

A classroom today might well have the gender balance of HaCF’s opening scene. When I got my computer science degree in 2004, I was often the only woman in the class, or one of two. As of 2012, only 18% of degrees in computer science went to women. But that’s not the way it’s always been, and the change happened right around the time HaCF is set.

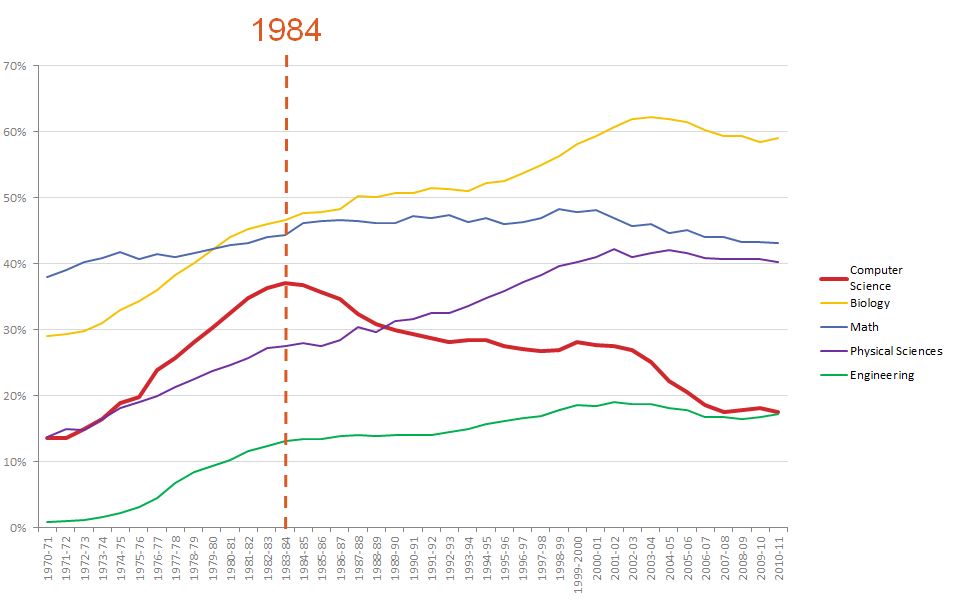

It’s important to realize that this change is absolutely unique to computing. This is apparent when the graph is compared to other science and technology fields. Physical sciences and biology show steady growth in gender equality, while math and engineering have mostly flattened out. Only computer science and information technology shows a peak and a drop. Why did this happen in 1984?

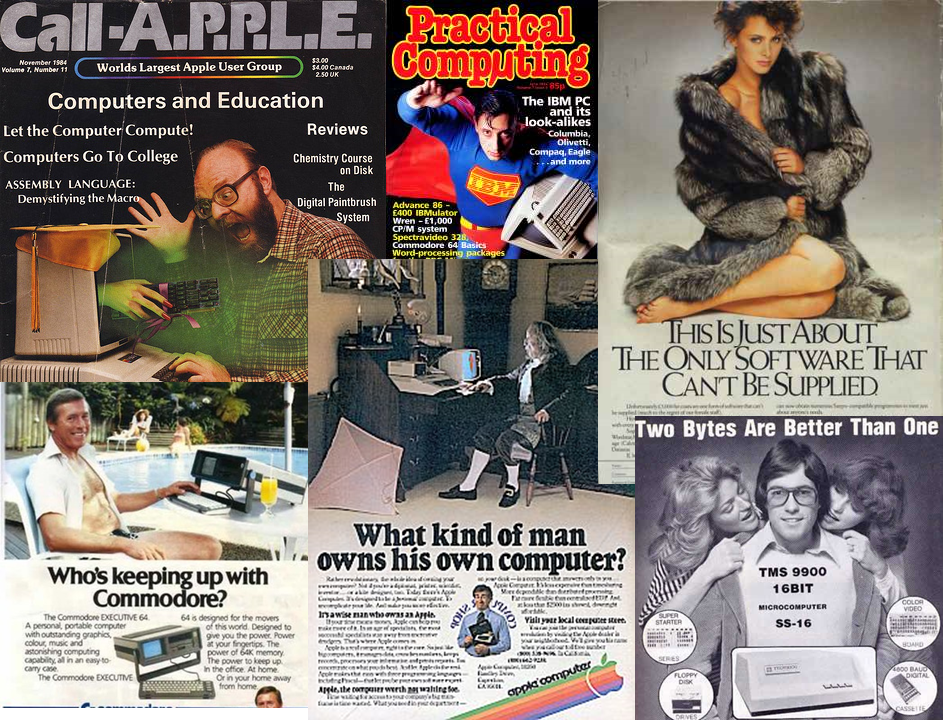

Well, there’s a reason that HaCF is set in this particular year. It’s about the moment that personal computing exploded, and 83-84 saw a jump in PC sales that wouldn’t slow down for decades to come. In 1981 “The Computer” was Time’s Machine of the Year (in place of a Person of the Year). This was the tipping point where computers went from specialized equipment to something most Americans knew about and encountered in their everyday lives.

So here’s something that separates computing pre-1984 from either computing post-1984 or other scientific fields: it was new. There weren’t a lot of stereotypes yet about who used computers, because they weren’t represented all that much in popular media. The early to mid 80’s is when that changed. The next few years saw movies that jumped on computers and videogames as cool new trends.

The 70’s and 80’s saw an increase in women’s participation in most technical fields. The biggest difference between computers and, say, physics is that physics had been around a lot longer, and people had already developed and popularized ideas about what physicists look like. Computing was new, and those ideas were still in flux. In the 50’s and 60’s, most of the early programmers were women. Perhaps that’s because early programming looked a lot like operating a telephone switchboard, which was a female-coded task at the time. Between the 60’s and the 80’s, programming started to be associated more with math, a male-coded task, and more men were hired into those jobs.

By the 80’s, that was already changing again; the growth of graphical user interfaces and applications of computers to a much wider variety of workplaces made all kinds of new skills relevant in computer science. A lot of it started looking like design, or engineering, or ethnography, or psychology – enough different elements that it was its own new thing, without obvious gendering or stereotypes attached. Women and men alike flooded into this obviously growing job market. For a brief time, there was a space in which any number of stereotypes could have taken hold. And the media almost immediately filled it with male power fantasies.

Whatever the reason, the media quickly hit on a standard trope for what made computers cool: they were magic items that allowed weak and/or socially awkward men to obtain great power. The guy who always got kicked around now could use specialized knowledge to make money, wield military power, and get the girl. These were all key ideas in advertising of computer products in the 80’s too.

Let’s get back to the tough, brilliant, always exceptional Cool Hacker Girl. Women in these first computer movies were mostly just love interests, the prizes that men won by being good at computers. But as the 80’s turned into the 90’s, the cyberpunk aesthetic got pulled into computer movies. Now the hacker team of disaffected dudes started to have a single woman on it, and she started to fit some recognizable tropes: short hair, tough demeanor, lack of traditional feminine interests, a sense of defensiveness. People often mistake her for a man, or are surprised to find out she’s a woman. Most or all of her relationships are with men. The men who surround her often talk about her with awe.

The most direct ancestor of all these characters is Molly Millions from William Gibson’s Neuromancer, which encoded most of the tropes of the cyberpunk genre back in 1984. Lauraine LeBlanc’s Razor Girls: Genre and Gender in Cyberpunk Fiction outlines the character type and how it relates to femininity and masculinity. But there’s a broader tradition these character tropes borrow from, and it should be pretty familiar to nerds: the (exceptional, unfeminine, tough-as-nails) lone woman warrior.

Of all the stereotypes of women out there, it’s hard to think of one that’s influenced my life more negatively than this lone woman warrior / hacker type. I relate to a lot of the experiences in Jenn Frank’s I Was a Teenage Sexist. A lot of those issues I went through as a teenager were encouraged and fed by that sense that my interests in nerdy things made me separate from and superior to “typical” women. For a long time I saw the world the way early HaCF episodes see Cameron’s world: boring women in perfect clothes oppressing me while I fought my way into a world of men where I belonged. All this required some mental effort to believe, since as a kid and a teenager I was surrounded by women who shared my interests. But any way they differed from me was a sign of their girliness and hostility towards me. There were other reasons I felt isolated from the people around me, but I didn’t see stories about those reasons. I did, on the other hand, read a hell of a lot of fantasy and scifi novels about girls who got knocked around for being too good at being like the guys.

The woman warrior is a trope that simultaneously reinforces the myth that women are not normally fighters and portrays the life of a woman fighter as difficult and undesirable. It’s the exception that proves the rule in worlds built on the lie that Kameron Hurley tears apart in We Have Always Fought. The person “stuck between worlds” – one to which they naturally belong, and one relatively more privileged – is a common stereotype wielded against marginalized people in fiction. Typically the unresolvable problem presented by the narrative is solved by the marginalized person dying, sadly resigning themselves to one of the two worlds, or finding happiness in a marginalized existence.

In updating these character tropes for the computer era, media positioned computers and technology as having very different relationships to men and to women. For the male hacker wizard, the computer is a spellbook. It becomes a device for explaining how the weak, underdog man gets power over other men. This power sometimes takes the form of approved male power fantasies: sexually available women, military victory, money. Other times, the power of technology is its own end. This power has been unfairly kept from him because he is physically weak or uncharismatic. The conflicts that arise reflect typical conflicts in stories about magic, such as the need to get a powerful object from an opposing wizard or fears about how power corrupts. War Games, for example, is just the story of a novice mage who toys with power greater than he understands, accidentally summons a demon, and must trick the demon to stop it from destroying the world.

The adaptation of the lone woman warrior into the cool hacker girl works differently. The warrior woman is often an exceptional fighter, but her power is not overwhelming or associated with dark forces. Trinity is great at using the Matrix, but Neo has power that upsets the balance of the entire universe. Women hackers rarely revel in power for power’s sake. They just want to get the job done. Usually, that’s a job given to them by a male protagonist. Their skills prove useful to others, but they pay the price of becoming outsiders. They are rejected by and separated from other women, but constantly have to prove themselves to the men that surround them. A woman wanting both technical skill and a sense of belonging is presented as an unsolvable problem. In the end, both hacker girls and women warriors either end up tragically alone (Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Molly Millions), “fixed” and made more traditionally feminine by a relationship with a man (Eowyn, Kate from Hackers, Disney’s Mulan), or martyred (Joan of Arc, Trinity). Good luck, Brienne!

Throughout the first two episodes of HaCF, Cameron is repeatedly shown as trapped between two worlds, neither of which fully accepts her. Her professional peers are mostly men, who treat her as strange and disruptive but who aren’t actively sexist towards her. But the show goes out of its way to depict other women as hostile to and separate from Cameron. A perky administrator needles her about her clothes. Women stare at her whenever they see her. In the strangest example, the character Donna initially assumes Cameron is a man based on her husband’s description, and her husband doesn’t correct her. Later she meets Cameron and learns the truth and – in a truly baffling scene – her husband confesses (?) that Cameron is a “girl” and apologizes (?). Donna seems shocked and threatened.

None of this makes any sense at all. Donna, we’re told, is an engineer herself, so why is she so surprised that another woman is a programmer? And why do both she and her husband treat the lack of disclosure as a betrayal? The presence of a woman in this space is treated as a dangerous anomaly by itself. Their conversation might make sense if Cameron concealed herself as a man to enter some all-male-by-law order, so that’s what these scenes end up implying.

Tons of research has been one over the years on why women in the United States are so underrepresented in computing fields. It’s clear that they get pushed away from the time they’re children to the time they get a job in the tech sector. There are a lot of interlocking factors that cause this. Parents and teachers encourage and recognize kids’ skills differently based on perceived gender. Sexism, both overt and subtle, in computer science departments and tech companies makes those environments hostile to women. Media stereotypes enter into a feedback loop with these systemic factors. Media tells people what’s normal, people adjust their expectations, they behave based on those expectations, and the world looks more like media’s idea of normal. Keep this up for thirty years and who knows what can change.

In a 1997 Carnegie Mellon study of factors leading to under-representation of women, researchers asked college students what drew them to computer science as well as what they didn’t like about it (quotes taken from these two papers). When they asked men why they liked computing, they said things like,

“I like just what a computer can do. I don’t know why it interests me so much…They say kids like to take things apart and see what makes them go and I do that a lot….”

“Well, I think it was sometime in middle school, sixth grade, about then, my dad borrowed a computer from a friend, it was an old black and white Macintosh, just totally self contained one unit thing, and I remember just playing with that all the time and trying to figure stuff on it. And that got me really hooked…I was really getting into figuring things out on computers and I just knew that that was going to be something for me.”

When they asked women, they said things like,

“The idea is that you can save lives, and that’s not detaching yourself from society. That’s actually being a part of it. That’s actually helping. Because I have this thing in me that wants to help. I felt the only problem I had in computer science was that I would be detaching myself from society a lot, that I wouldn’t be helping…”

And when they asked women why they were considering leaving, they said things like,

“In my free time I prefer to read a good fiction book or learn how to do photography or something different, whereas that’s their hobby, it’s their work, it’s their one goal. I’m just not like that at all; I don’t dream in code like they do.”

“I began to lose interest in coding because really, whenever I sat down to program there would to tons of people around going ‘My God, this is so easy, why have you been working on it for two days, when I finished it in five hours’ and ‘Geez, you’re such a terrible hacker, you must have only gotten into SCS because you’re a girl,’ and so on.”

Men revel in the power of programming for its own sake. Women worry about being isolated and forced to be single-minded, and have their skills constantly questioned. Men feel excessively confident about their skills and pressured to brag about their power, leaving women feeling like they’re behind even when they aren’t. They internalize these stories about themselves and each other, and their expectations shape the world around them. Men’s confidence in their abilities grows out of proportion to reality; women lay down their swords and return to the world.

As a teenager, this worldview fucked up my relationships with women in ways I’m still recovering from. It also made me vulnerable when I got into computer science in college. There my classes had the gender balance that HaCF erroneously attributes to 1983. With my identity all wrapped up in shit about not being like other girls, I let slide a ton of sexist, aggressive, and harassing behavior from my classmates. One of them groped my breasts outside of a classroom one time, while students milled back and forth around us. I laughed it off, which astonishes me now. I think it honestly didn’t occur to me that I had any option available to me besides adapting to whatever happened. I was in someone else’s space.

The classroom in Halt and Catch Fire’s opening scene wasn’t the world that real Camerons lived in. But people making media thought that was probably the way things were, or maybe the way they should be. So they made image after image of this world that didn’t exist. Twenty years later, that world was reality. These images matter. They tell people what normal is, and what people think is normal is shapes how they behave. This isn’t a game. This is how we forget history.