MIXTAPE: You Lose for Playing

June 17, 2014 - Mixtapes

Execution, Jesse Venbrux (2008)

Over the years, I’ve played or read about a lot of games that push the player to feel bad or conflicted about doing the things the game allows. The idea fascinated me when I first played Bioshock; by the time I watched my boyfriend play Spec Ops: The Line I had already tired of it. In between I played Execution, a game which presents the “you lose for playing” idea in its most concise form. I’m fond of Execution because it was the first game I ever wrote about here. Since its theme became a cliché, I can’t return to it with the same eyes. I’m also not sure I like how the game affected me anymore. It did push me to notice my instinct to do violence in order to advance. But mostly it struck me as very clever, and I was curious about how the restarting trick worked. (The game writes a registry key.) Being presented with something clever and figuring out how it works makes me feel good, not bad, about myself. Maybe the game would have felt different if I hadn’t figured it out – more mysterious, maybe. I also might never have found the alternate path. I don’t know. Discomfort and cleverness don’t always work well together.

Savior, mtarzaim (2012)

Savior combines a You Lose for Playing mentality with my all time favorite videogame trope, the Groundhog Day loop. The central loop is a short one, but you get a lot of variations on how to play that out. Every time you complete an action, the game ends and starts over. The characters start to notice the repetitions and freak out. They start blaming each other. Sometimes they attack your avatar or just yell at him, sometimes they fall into sullen silence. Meanwhile I found I could get a torch from the firepit and set fire to every object in game, one loop apiece. By the end the characters are all screaming directly at me, the player, begging me to release them from the endless cycle. The only way I can do so is to quit the game, of course. The specific thing that Savior wants to implicate the player for is the process of replaying. It’s interesting how this plays off of Execution in a way. Execution sees replaying as an attempt to evade moral responsibility; Savior sees it as sadistic.

Princess Queen, Merritt Kopas (2012)

This is kind of a weird one, really, since it’s just a normal little Glorious Trainwreck-style game with a twist at the end. Of all the games here, Princess Queen most highlights the goofiness of the “you lose for playing” premise. It doesn’t mean anything if you turn out to have been bad all along, if the world doesn’t make much sense to begin with. Why do I even read the glowing green eye as bad anyway? It just has a big font! I’m being totally unfair.

Run, Christopher Whitman (2012)

For me, Run is the most successful of the games here at making the “playing” part compelling enough to make the “you lose” sting a little. I find the minigames in Run all really engaging. In one type of segment, you play a series of interconnected classic arcade games. The centipede you finish with becomes a stage for a little platformer, while the centipede itself has to dodge the remnants of the space invaders you left behind. How well you do on these segments determines how much sun yo have for the next segment type, a quick farming sim. The outcome of the farming sim determines how many of your villagers survive. I found it hard not to do as well as I could on all these games. I wanted to keep my people alive, and I liked playing them. The act it condemns, really, is giving to the seductive idea that problems can be solved by doing stuff that feels satisfying in games. Wouldn’t that be nice?

The Duck Game, James Earl Cox III (2013)

What have you done? You have held the duck again, despite your many attempts to quit your addiction to duck-holding. Like Execution, you have the option of quitting before your inevitable failure, although in this case the game informs you of that option.

Why would you do such a thing? Upon holding the duck, you are rewarded with a pleasant scene where you and the duck can fly through a colorful cloud-filled sky for as long as you like. It gets repetitive after a while.

Are you not ashamed? lol no [GIN INTENSIFIES]

FRUIT MYSTERY, Brett T. Graham (2008, maybe?)

In FRUIT MYSTERY, you feed inappropriate fruits to a large number of zoo animals. You do so zealously and without care for the future. The inappropriate fruits cause untold harm to the animals and the zookeeper is very angry. The game explains all this clearly. But you saw a fast-moving series of animals and fruits, and matching fruits to animals produced amusing messages. Despite every critical instinct in my body telling me to try every game with multiple strategies, I have never been able to play FRUIT MYSTERY without feeding the animals fruits. FRUIT MYSTERY understands: we do what we do in games because doing things we are told and receiving positive feedback is delightful. Well. For me it is. Perhaps that bears examination.

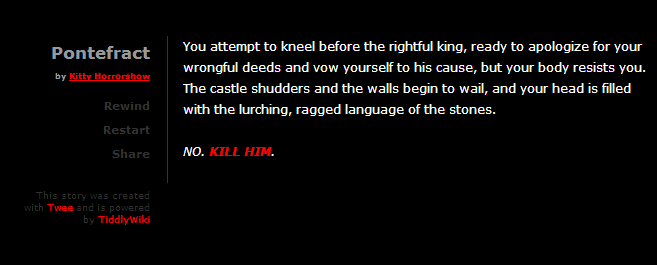

Pontefract, Kitty Horrorshow (2012)

Pontefract isn’t about punishing the player, but depicting a punishment. The protagonist seems to be caught in an afterlife dedicated to tormenting them for assassinating the true king, one in which they commit their crimes over and over. While each of their victims initially appears harmless, approaching them with anything other than murderous intent will reveal them to be demons that immediately attack the player. By the time you get to the true king, you have no choice but to kill him. The world contains a justification for your sins – I had no choice, they were evil – so in a way it could be a story the killer tells themselves for comfort. But the justification comes in the form of more punishment. It could also be seen as a world that refuses to let the killer have the comfort of imagining things happening another way. There’s nuance in that ambiguity, and insight into the nature of self-punishment.

Puppy Shelter, Stephen Lavelle, (2011) [Content Warning: animal cruelty]

Puppy Shelter is a typical example of something Lavelle (aka increpare) does sometimes: he designs a really clever and satisfying puzzle game, then attaches really uncomfortable subject matter to it. You play for the thrill of completion, but then it gets undermined by an unexpected emotional tone. When I get a puzzle right in this game, I get excited, then I get 12 dead puppies. It feels weird and bad in a very specific way. I think Lavelle’s games have a stronger impact on me than others in this genre both because he deals in more familiar awful subject matter than something like Execution, and also because I get more pleasure from his puzzles than I do from shooting dudes.

Press X Not To Pry, Bento Smile (2010)

Press X kind of inverts the You Lose for Playing genre. It’s a game where you will do something bad if you fail to take the only action available to you. So really, if you play the game right (?), you haven’t done anything at all! If you lapse, though, you rudely observe an array of characters in embarrassing situations. The difference between Press X and its compatriots subtly changes the moral feel of the thing. The typical game in this genre presents bad behavior as mindless obedience, whereas Press X presents it as lack of restraint.

Mario Empalado, Pedro Paiva (2013)

A lot of games that implicate you for playing them fall flat because this is a weird mapping to most real-world moral situations. People do bad things for reasons, not because it is literally the only action available to them. Making a big deal of the latter situation can come across as either punishing someone for events they had no control over or justifying immoral actions by pretending the actor had no choice.

Mario Empalado‘s critique of consumerist gamer culture, on the other hand, is a pretty good fit for the “quit or do wrong” moral universe of these games. Participation in a culture is something you can enter into casually but which can shape your behavior in ways you don’t notice once you’re in it. Subtle isn’t what Mario Empalado is going for, but it does make connections between the process of consuming, doing violence, and feeling unpleasant. I have issues with some of the choices made here: given the broad dehumanization of your targets, it’s a bad move that the only named real people you kill are both Japanese developers, and that most of your other targets fit a “lazy gamer” visual stereotype that demonizes people based on weight. This game isn’t offering a better way of looking at things. Its function is just to make something you already do feel awful. As such, it inspires genuinely defensive reactions, as opposed to Execution and its descendants, which can make the player feel clever.

Further reading

Chris Priestman on Execution

Gregory Avery-Weir on Execution

Porpentine on Savior

Zolani Stewart on Mario Empalado

[Please suggest any links I may have missed in comments!]

![Press X Not To Pry screenshot. On the left, a blue figure wearing a horse mask and diapers stands between two open yellow curtains. A green slime with big eyes is on the right, looking embarrassed. The background is bright pink and the graphics are cute. Text at the bottom reads: "OH GOD!!! WHY DIDN'T YOU PRESS [X]?!? [Z] to retry"](http://www.linehollis.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Press-X-Not-To-Pry.png)