Leaning Games

August 30, 2011 - Features

AwkwardSilenceGames’ One Chance

The world of art games is young and vibrant, full of unique experiments. Still, if you explore the output of the experimental world enough, you’ll start to recognize a few common types. There’s the punishing platformer with dark themes; the aggressively unexplained low-fi puzzle game; the quirky Mario variation. But there’s one game type that threatens to become the representative cliche of the entire art games world: let’s call them leaning games.

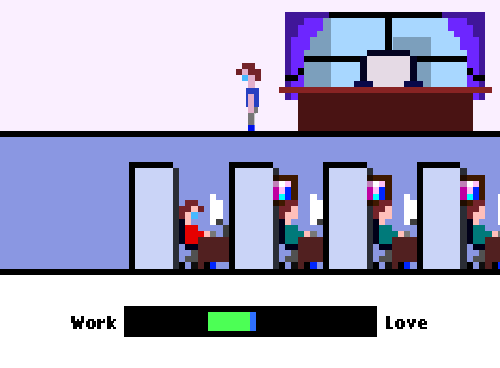

In a leaning game, you are a guy (almost always a guy), going through your life. Your story is mostly told to you passively or with minimal interaction. Every once in a while, you are given the opportunity to make a choice between two alternatives. These choices are not presented dramatically. You decide whether to stay home or go to work, or whether to slack off or try hard. They aren’t grand moral decisions, but rather, a gentle leaning in one direction or the other. Nonetheless, their implications to the story are telegraphed clearly. The sum of these choices is used to select between two or more endings to the story. Frequently, you encounter sad music, pixel art, and angry wives.

The best known examples are Terry Cavanagh’s Pathways and AwkwardSilenceGames’ One Chance. Pathways is a bit unusual in that it sends you careening through a more chaotic story space than you usually see. Still, it was one of the earliest examples of this type of game and had an undeniable influence on subsequent versions. In Pathways, your choices come in the form of forks in the road that take you to different outcomes. Unlike many of the games that followed it, Pathways actively encourages you to try out all the different paths.

Although it would eventually prove to be an outlier in some ways, Pathways established the basic model for leaning games. Seemingly minor decisions took you into very different endings. They have a cumulative effect. Some of the decisions involve choosing between women, and choosing between women and work.

One Chance shares this basic model, but unlike Pathways, strongly discourages exploration of different story paths. It also provides a more cohesive storyline and a serious tone. Now your choices are focused on affecting a single outcome: whether you discover a cure for the plague you caused. Over time, these elements have become characteristic of this type of game.

Jonathan Giroux’s Lifetime

Although One Chance features a much more dramatic storyline than most leaning games, it still features the same kinds of choices. Do you work hard, or spend time with your family? Fool around with the coworker, or go home to your wife? Are you obedient or rebellious? These are the choices that appear over and over in typical leaning games such as Convergence, Distance, and Lifetime. The same basic model applies to many visual novel games from the experimental world, such as Bento Smile’s Air Pressure and The Life of a Pacifist Is Often Fraught with Conflict.

Why is this particular model so ubiquitous? In a way, these games descend from the basic Choose Your Own Adventure style, applied to different kinds of stories. But for the most part, these games don’t involve extensive storyline branching. Your decisions don’t constantly open up new possibilities or close others off. They just declare a moral leaning in one direction or another. And there are often significant stretches of the game where you make no decisions at all.

What this style really resembles is the story structure found in mainstream games with a “moral choice system,” like Bioshock, Infamous, or Mass Effect. The dead simplicity of the system in Bioshock is a particularly close match. Each Little Sister offers a chance to lean in one direction or the other. Your decisions to save or harvest the Little Sisters only barely affect the storyline, but they do affect which ending you get.

In the shooters that employ this structure, the leaning moments are used as a crude way to make the player feel involved in the storyline. If it works, this helps to motivate the player’s desire to complete missions. Leaning games take this basic structure and strip out the intervening gameplay. The gameplay exists solely in the moments where you declare your moral leaning. This has the effect of magnifying issues with this storytelling style, which by itself would make these games a valuable experiment.

streetlightstudios’ Convergence uses a common theme of work-family balance.

Something else happens in the translation from Bioshock to a ten minute art game, however. I’ve already discussed the fact that these games tend to return again and again to the same themes: work-family balance and loyalty vs. adultery, in particular. I believe this is a consequence of the developers wanting to make serious games. At heart, leaning games are an attempt to translate certain qualities of AAA games to something that feels artistically respectable. And as producers of Oscarbait films and bestselling books have long known, domestic drama is the quickest route to an audience’s respect.

This time-tested strategy has an odd effect when combined with the leaning game structure. Domestic dramas are generally built around small moments that express character conflicts, like disagreements, apologies, and things left unsaid. Too many large-scale events would seem melodramatic or implausible. So leaning games made in this genre need to include a lot of decisions about small things. Usually a book or movie in this style would include one or two big events that bring these conflicts to a head or resolve them. But leaning games also borrow from a style of game storytelling in which decisions made throughout the game all happen at roughly the same dramatic level and cumulate to determine an ending. There’s no room for car crashes or screaming fights in these games. Only a series of small moments that together determine an outcome.

The end result is that all leaning games express the thesis that the major events in your life are a sum of the minor decisions you make. This is a perfectly reasonable thesis for a game to have. My concern is that this thesis is rarely explicitly dealt with, possibly because the designers aren’t aware that they are making it or what its implications should be for their story.

This specific problem doesn’t usually happen in the mainstream shooters from which leaning games borrow their structure, because your character is generally The Most Important Person in the World. Your character’s importance explains why even their minor decisions can have a dramatic impact on the ending of the game. One Chance does the same thing, which is why it feels more satisfying than other games in this genre.

There is nothing wrong with trying to be subtle about the point your game is making. Still, I’m not convinced that most games in this genre are intentionally making this point at all. Maybe Distance is about the fact that long-distance relationships are particularly sensitive to small choices that reflect the long-term attitudes of the couple. But the game itself provides little evidence for or against this interpretation. Maybe Lifetime and Convergence are trying to say that small choices shape your character, or that small choices reflect your character. Neither game commits to one thesis over the other, nor do they outright address the question.

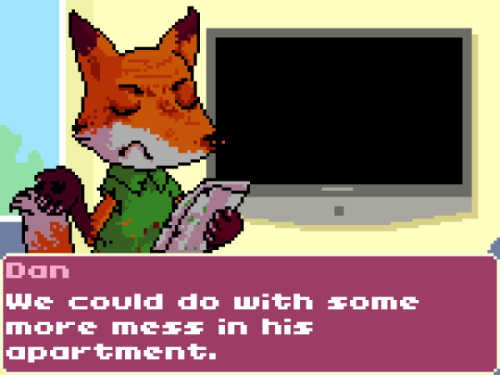

The Life of a Pacifist Is Often Fraught with Conflict

One game that does deal with this thesis is The Life of a Pacifist Is Often Fraught with Conflict. In Pacifist, you play as an employee at a game company who is ambivalent about the violent game on which she’s working. Your leanings come in the form of thoughts or comments about your co-workers’ delight in designing something gory. If you lean in the direction of revulsion, your co-workers begin to appear more and more monstrous. If you lean in the direction of acceptance, they continue to look normal. Your comments have no effect on your co-workers, but if you stick with your feelings of revulsion, your character works up the courage to quit at the end.

This adds up to a cohesive argument about how small decisions can lead to larger outcomes. Your thoughts and moral leanings affect your view of the world. That worldview in turn determines your major decisions. If you try to calm down and be a team player, you forget why you objected to the violent game in the first place. Stating your principles might not affect those around you, but it does affect who you are and what you’re capable of. It’s a small game, but one that has some psychological weight to it.

Pacifist shows that there is potential to the leaning genre. The simplicity and narrative quirkiness of these games are not inherently bad things. But to avoid slipping into cliche, designers need to address the implications of the form, both intended and unintended.

[Note: This post originally appeared at a now-defunct site called Robot Geek. I’m gradually backing them up here.]