Game Stories and Fortunetelling

August 9, 2011 - Features

One of the reasons it’s hard to tell stories in videogames is that there are so many variables flying around. You want to give the player a sense of freedom in the story space; but the more freedom they have, the more changes to the world you have to track. Is so-and-so dead or alive? Does this person like you or hate you? Does this town still exist? Did you do that quest? How do all these things affect the part of the story you’re in now?

Games with a branching story style manage this by limiting the number of points where variables can change. This works, but it feels less free. More open-world games just monitor a huge number of switches and produce variations on story events based on the game state. This can make the world feel more responsive, but it’s messy and hard to manage. I suspect the use of this strategy has a lot to do with the weird quest-breaking errors associated with Bethesda games like Fallout: New Vegas.

Both of these strategies arise from a desire to explicitly acknowledge changes in the game state. They assume that if the game doesn’t demonstrate clearly that it knows what has already happened, players won’t believe that the story holds together. But there are more subtle ways of dealing with messy storytelling spaces. The Persona series of Japanese RPGs does a particularly good job of dealing with an uncertain storyline without getting bogged down in branching points or state variables. Moreover, I don’t think it’s any coincidence that you see this working so well in a game that bases so much of its mechanics on Tarot cards.

Persona 3 and 4 use Tarot cards for a lot of things in the gameplay, such as classifying character types, connecting the social sim to combat bonuses, and selecting rewards at the end of battles. But it also seems to have learned some lessons from fortunetelling when it comes to the story. After all, a fortuneteller faces a lot of the same narrative problems as a game designer. You’re telling a story about your audience, and you need to adapt to their reactions without being too obvious about it. Most importantly, you’re missing key information about the audience’s prior experiences and expectations: information that determines whether your story makes any sense.

Edogawa, one of the teachers in Persona 3, explains the basics of Tarot card reading.

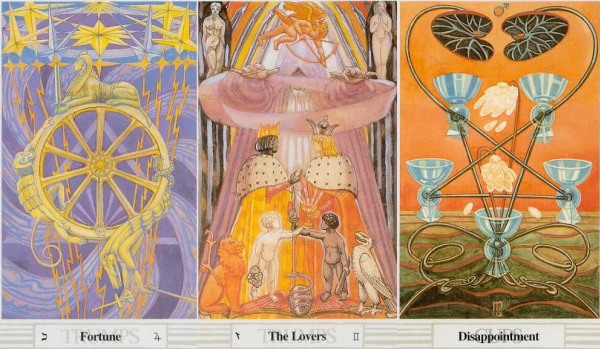

Fortunetellers have a lot of techniques for managing this, but a lot of it boils down to maintaining a particular level of ambiguity. You need to be specific enough that the client feels that the story is uniquely about them, but vague enough to apply to many different situations. If you hit that sweet spot, the listener will do your work for you by interpreting your words in relation to their own lives. Similarly, Tarot art is about creating images that are just abstract and archetypal enough to fit into many different stories, but specific enough that they give the reader something concrete to work with. Designing a deck of Tarot cards is about creating a possibility space. It’s a lot like making a narrative game that way.

Boy meets girl. From the Book of Thoth Tarot deck by Aleister Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris.

So how does this work as a game storytelling style? Well, here’s one little story I came across in Persona 3, with very light spoilers. Persona 3 has a pretty typical anime-style plot about a bunch of teenagers fighting demons and whatnot. The hero is the new kid at school who joins the team at the beginning. My hero was initially unimpressed with most of the other characters he came across, including the lovely Yukari, whom the game pushes pretty hard as a potential love interest at first. Yukari struck me as a flake and I pretty much either ignored or fought with her throughout the beginning of the game.

Then there was a little interlude in the game where all the characters go off on vacation and learn some shocking things about the backstory, which Yukari got very upset about. My hero felt sympathetic towards her, especially since she seemed to be the only one who found the backstory as alarming as he did. So he chased her down, they had a little romantic moment at the beach, and when they got back he expected this romance to continue. But back at school, with her emotions back under control, Yukari spurned him, and he (and I) stormed off in disgust.

Boy somehow loses girl without getting her in the first place.

This is a perfectly cohesive little subplot in a story the size of Persona 3‘s. It’s a familiar bit of teenage romance: you go away to camp or vacation, fall inexplicably hard for someone, then go right back to normal when school starts again. But none of that was explicitly written into the game. This particular story depended on a lot of variables: the fact that I wasn’t friends with Yukari before the vacation, that my Charm wasn’t high enough to win her over afterwards, the fact that I wasn’t already romancing another girl.

But the game didn’t care about any of that. Rather than use all those variables to select an appropriate scene, the designers just wrote the scenes in such a way that they fit into all these different scenarios. The scene with Yukari on the beach is ambiguous enough that it works if you’re already in love with her, if you’re with someone else, or if you’ve spent the whole game fighting with her. Yet, it doesn’t feel vague or generic. Like a good Tarot deck, the game gives you materials that can make a story concrete without having to know what the story is.

Doing this kind of writing well is a unique craft, and I can’t pinpoint exactly what makes it work in the Persona games. And it can certainly break if the player’s expectations diverge sufficiently from the designers (as happened to me rather spectacularly in Persona 4). Still, that kind of breaking is preferable to the kind that occurs when the Fallout: New Vegas quest system gets overwhelmed by story flags. A story that confuses or frustrates me can be interesting; a story that doesn’t end because I’m wearing the wrong hat can’t.

Narrative game designers are putting a lot of faith in variables these days. That can be fun, but it tends to result in games that are either incredibly buggy or incredibly restrictive. Figuring out how to design for ambiguity might produce more bang for the buck. The biggest lesson game designers can learn from fortunetelling is that you don’t have to know everything about someone to tell a convincing story about them. In fact, you don’t need to know anything. You can get pretty far by faking it.

[Note: This post originally appeared at a now-defunct site called Robot Geek. I’m gradually backing them up here.]