Surrealism from the Inside

June 27, 2011 - Features

Amanita Design is a developer known for its charming little point-and-click adventures. The games are distinctive for their low-key surrealism and collage-like art style, but as games they tend to be very simple. You manipulate the environment by clicking on hotspots. Click them in the right order, and you can progress to the next screen. By including an avatar and inventory system, the feature-length Machinarium more closely approaches a traditional adventure puzzler. But Amanita’s shorter pieces, like the Samarost games and the recent Osada, don’t involve anything more complicated than pixel-hunting.

These are the kind of games that people are sometimes reluctant to call games. On the Amanita Design website itself, Osada is described as an “interactive music video.” Indeed, it’s not hard to imagine Osada working just fine as a Terry Gilliam-style animation with no interactivity at all. Just automate the clicks.

Earlier this week, Fraser made the case against this kind of thing in his piece on medium specificity. Good games are those that do things only games can do, the argument goes. Trying to imitate or adapt styles from other media leads to creative stagnation. A weird hybrid like Osada, by trying to be both game and cartoon, fails to be a good example of either.

I have a lot of sympathy for this viewpoint. I’m fascinated with experimental games largely because they’re so efficient at figuring out what games can do that other media can’t. At the same time, I think hybrids actually can tell us a lot about the differences between media, in a way that “pure games” can’t.

Take Osada. It might well work as a non-interactive animation. But would that be the same as playing it? I suspect it wouldn’t. Adding interaction changes how you view a scene. If you watch someone else play Osada, your eyes will probably focus on different things than if you play it yourself. Playing an Amanita game gets you looking for things that look like mechanisms or gates. When you’re passively watching an animation, you tend to focus on things that are moving. But in Osada, you look for things that could move; things that are already moving are out of your control, and therefore less interesting.

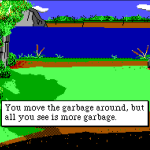

A baffling scene from Osada.

A baffling scene from Osada.

Osada, like the Gilliamesque cartoons it resembles, is a string of events that follow a surrealist logic. Causes lead to effects in a weird way. Some freaky sausage-plants grew, and then some bearded bees showed up. Okay! If you’re mostly following the things that move, you’re focusing on the effects: plants grew, some bees flew into the frame. You don’t have to think about the logic if you don’t want to. You can just perceive it as a series of odd things happening. If you’re looking for things you can click on, it shifts the emphasis onto the causes. Clicking on the ground made the plants grow. That made the bees show up.

The end result is that playing Osada, rather than watching it, directly teaches you the surrealist logic it operates under. For good or ill, you’re focused on why these weird things are happening. This isn’t a dramatic difference. But it is a difference, and it tells you something about what games can do better than cartoons.

Games that focus on being gamelike are absolutely vital to advancing the medium. But games that borrow from other media have their place as well. Whether they fail or succeed at being good games is almost beside the point. By reducing the amount of difference between games and another medium, these border cases cast the differences that remain in sharp relief. Something that almost isn’t a game can you a lot about what a game is.

[Note: This post originally appeared at Robot Geek. I’m gradually backing these up here.]