Reading Mad Men: “The Wheel” and The Wheel of Fortune

February 27, 2015 - Features / Reading Mad Men

PETE’S FATHER-IN-LAW: Nixon didn’t stand a chance. The Browns trounced [Washington], 31-10. The result of that last home game has correctly predicted the last six elections.

PETE: I wish someone would have told me that.

[both laugh]

PETE: …of course, it’s really a 50/50 chance of being right.

The climax of “The Wheel” is an especially key scene within Mad Men as a series. Don delivers an emotional pitch for an ad strategy for a Kodak slide projector that incorporates his own family photos. He talks about nostalgia, defines it as “the pain from an old wound,” and calls the slide projector a time machine that takes us back to where we belong. He then suggests naming the projector the Carousel, associating it with childhood and play. The customers are stunned. TV critics are stunned. The scene summarizes the major themes of the show and, in-universe, establishes Don’s reputation for creative brilliance. It’s a peak he’ll spend the rest of the series trying to return to. Then he goes home to an empty house.

In the tarot spread in “The Mountain King,” the Wheel of Fortune comes up as the card that represents Don’s hopes and fears. The Wheel of Fortune is the tenth card of the Major Arcana, falling in the middle of the 22-card progression. It’s associated with luck, gambling, sudden changes in fortune, and the cyclical view of time. It can suggest both chance and randomness as well as the unseen motion of fate. Part of Don wants the stability of that traditional family life in the slideshow, as his fantasy at the end of “The Wheel” shows. But he also takes every action he can that leads him away from it. He wants to believe everything can change in a moment, but he’s afraid of that happening without him controlling it. The pitch scene ends with Harry, a younger man taking his first steps towards Don’s shitty life, bursting into tears and running away. Harry’s faced with a future he’s already lost, while Don looks to a past that never really existed. They’re mirrors on opposite ends of the wheel.

Like the product it’s named for supposedly does, “The Wheel” acts like a time machine in the show. The dense network of foreshadowing in the episode means that in some ways, it contains the whole series in obscured and abstracted form. Likewise, there will be callbacks to the events of this episode for the rest of the series and the ten years it spans. Like The Wheel of Fortune in the Major Arcana, it represents a turning point and key change in fortunes in the story. But, characteristically of Mad Men, those changes aren’t presented in a traditionally satisfying narrative arc. Peggy’s pregnancy seems to come out of nowhere; Don’s split with his family won’t be resolved for years; and both will see their careers go through the same patterns they hit here many times over. Through a variety of techniques, most of which are on display in “The Wheel,” Mad Men will continually force its characters into a chaotic, cyclical view of biographical narrative. Over time, this storytelling approach resists traditional resolution to make an argument about how people can change themselves.

I’ve been watching a lot of Mad Men episodes out of sequence for this project. It’s startling, every time, to see characters at different time periods in this show. So much TV happens in a fluid time-distorted space. Kids who look like adults are in high school for decades, while Sansa Stark shoots up a few feet in what seems like a month’s worth of story. Much is sacrificed in pursuit of the illusion that time moves continuously when the season is airing and freezes between finale and premiere.

But Mad Men moves its timeline more methodically. In-universe months pass between episodes, and the gap between seasons varies between a month and two years. Something happens to someone, and by the next time we see them, it’s become familiar to all the characters. We don’t get used to Peggy’s pregnancy or Ken’s eyepatch along with the characters, they just hit us one day. We’re flipping through old photographs, with all the random gaps in time that come with that. We forget to take pictures for a few months and suddenly everyone has beards. I mean, that’s exactly what my parents’ family photo albums look like.

Part of the reason for this is in the visual storytelling. Mad Men, especially in its earlier seasons, often uses a very flat visual style. More so than other shows, it leans on strong bright lighting that fills the scene, with a high depth of field that keeps all the actors and set pieces in focus. This style is especially common in daytime scenes in the office.

This flat style is partly used to make Mad Men more period-appropriate by recalling the look and feel of mid-century melodramas. But it does other things as well. In contrast to the flat style, the more common modern style is more aggressive about directing the viewer’s eye to certain actors or objects. It darkens or blurs parts of the scene you’re not supposed to look at, so they don’t register to your attention. By contrast, the flat style frames elements as more or less important more subtly, through cues like spatial arrangement and color. Because of this, the viewer’s attention can wander, and visual information can be introduced as an aside instead of only as a shout.

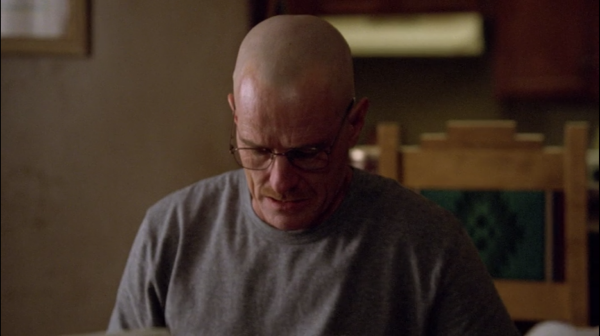

To take an example: when Walter White’s shaved head is first introduced in Breaking Bad (in Season 1’s “Crazy Handful of Nothin'”), it is not only given attention in the script and the actors’ performances, but in the frame as well. In these initial shots, Walt is the only object in focus. A strong directional light is used to literally highlight his newly bald head, placing most of his face in shadow. The framing in this shot is tight, and his head is aggressively centered. This shot also roughly represents a point of view angle from Skyler or Finn, and in the scene, it’s alternated with reaction shots from the other actors. All of these factors combine to visually shout LOOK AT THE HEAD LOOK AT IT!

The first scenes where Ken’s eyepatch is visible (in Season 6, “The Quality of Mercy”), on the other hand, are shot in Mad Men’s typical flat office style. The first shot is a closeup of the back of Ken’s head, and ends with him turning around for a relatively dramatic reveal (although it’s played low-key by Aaron Staton). But the very next set of shots clusters both actors and all the visible set dressing in a very shallow plane with everything in the scene at the same level of focus. Likewise, everything in the shot is equally strongly lit. Ken’s face is as clearly defined as the binder on the table next to him. Another crucial difference between the two scenes is that we’re never given a shot that represents Pete’s point of view, the way the initial shots of Walt represent his family staring at him in shock. In the Mad Men scene, our view comes from outside the characters.

This is why Ken’s lost eye feels, in the long run, about as important as Pete’s thinning hair. It’s introduced as part of the scene, not a singular object of attention. We aren’t invited into experiencing Pete’s shock along with him, and the change in Ken is almost immediately visually integrated into its environment. Although Peggy’s pregnancy-related weight gain is spread out over the course of a season, similar stylistic techniques contribute to the disorienting effect of the storyline. By letting significant character changes happen in this de-emphasized way, Mad Men implies that change is a continuous process, and not all changes are noticed by people who aren’t directly affected. Change in this show, both at the personal and societal level, is constant, chaotic, and often happens in the background. It resists the way change is used as fodder for story arcs.

Another way that Mad Men avoids telling stories with traditional resolution is by repeating the same patterns over and over. The show keeps coming back to themes of people who struggle to change and how patterns of abuse and destructive behavior still get passed between generations. Don inherits his father’s alcoholism and cruelty, while Betty internalizes her mother’s criticisms and passes them along to Sally. Peggy turns into her harshly judgmental mother when she’s angry with other women, showing flashes of her mother’s conservatism under stress even as she sees herself as progressive. Megan’s marriage gradually decays into an imitation of her parents’. The most pressing long-running conflict of the show is whether Don can change himself enough to keep Sally from repeating his mistakes. The idea that history is bound to repeat itself, embedded in the Wheel of Fortune, hangs heavy over the whole show.

Sometimes this use of repeating motifs can be frustrating. The same things keep happening. People fall into the same patterns over and over. It doesn’t feel like the characters are moving forward. It can feel depressing, even nauseating. It’s a feeling I appreciate, but I like feeling bad. It’s a kind of bad that feels familiar.

But Mad Men is also particular and self-referential enough with its motifs to feel artificial. It calls attention to itself. It wants you to notice what repeats, and how it’s the same, and how it’s different. It uses repeated shot compositions and costume cues to signal its repetitions, as Tom and Lorenzo’s fantastic visual analyses often highlight (for example, women carrying boxes filled with metaphors through the office).

Despite the way they keep repeating history, characters in Mad Men are typically pretty bad at seeing their own futures clearly. “The Wheel” is dotted with scenes where people predict the future. The Wheel of Fortune reminds us of the randomness that affects events, but people feel unduly confident in their predictions because they aren’t good at seeing randomness. Pete’s father-in-law has his theory about predicting elections. The slide projector itself is the future; Kinsey suggests a space-age strategy. At the end, Don imagines a warm homecoming that never happens.

The other predictions are just as imperfect. The rule referenced by Pete’s father-in-law will eventually fail, Don can’t go back in time and erase his fuckups, and in 40 years Kinsey’s slide projector will be a potent symbol of musty attics and dads. These predictions say more about what these characters want for themselves than they do about the future: certainty, a world full of possibility, a happy childhood.

At the same time, characters in the episode keep looking to images of the past. Betty digs up Don’s phone records, Peggy auditions voice actresses gushing about returning to their youth, and Harry gives a monologue on cave paintings that inspires Don’s nostalgia-based pitch. Don displays his family history to the customers. Like the predictions of the future, these interpretations of the past are unreliable and self-serving. Don’s performed memory of his family’s past is a selective one, chosen to express his wholesomeness (which he lacks) and traditional family structure (which, the series will eventually argue, everyone lacks).

The archaeology Harry refers to is just as distorted in favor of a comfortable narrative. In a fortuitous twist, between when I first saw the episode in 2008 and watched it again this year, new analysis has suggested that Europe’s first prehistoric hunter-artists were women, not men as originally assumed. It’s a wonderful touch that fits in with a lot of Mad Men‘s themes: the invention of gender roles, the invisibility of women’s achievement, how romantic views of the past serve to tell pointed lies about the present. It adds all kinds of layers to the scene, accidentally.

These faulty predictions and questionable archaeology all reflect a tension between the need to make cohesive stories out of events and the randomness of events as they really happen. A story is a chain of events that expresses a meaningful change between states. What type of change is meaningful depends on the teller. Usually people like the idea of a single person or group of people making the world more like what they want, or tragically failing to do so. Betty starts telling a story about herself by telling her therapist that she may be unhappy because Don is unfaithful, a story in which she can become happy by divorcing him, as she will in three years. But that isn’t what happens, because her unhappiness doesn’t come from a single source, and will persist when she has a faithful husband. Stories pretend that problems have a single source so that they can be defeated, but that isn’t how problems and change really work. Mad Men can be slow and frustrating because it tries to depict change coming from multiple pressures, problems caused by multiple sources, and the effects of random events on people’s lives.

Characters in “The Wheel” fail to see past and future clearly, and soon enough the episode’s events will become part of a distorted, propagandized past themselves. There’s Peggy’s ascension to copywriter, which a variety of people will take credit for over the years. There’s her pregnancy, which Don will advise her to forget, while she spends years trying to integrate it into her life story. And there’s the Kodak pitch itself, which will attain the status of legend in the show’s universe. In season 7’s “A Day’s Work,” Ken will eagerly show Don pictures of his own child and tell him that playground carousels always remind him of that day. Don responds awkwardly; at the time Ken brings it up, Don’s not sure what his status is in the company. The story of the young ad genius predicted by the Kodak pitch hasn’t panned out the way it should have. He’s neither a comfortable success nor a tragic failure who peaked too soon, just a guy who’s good at writing ad copy and has fucked a lot of shit up.

The memory echoes all the way to the end of the first half of season 7, “Waterloo,” when Peggy will give an emotional pitch that also alludes to a family life in deceptively traditional terms. Don will pass something of himself to Peggy in this episode, while Peggy transfers some of her feelings about the child she gave up for adoption to the neighbor kid Julio. People take each other’s roles; patterns continue regardless.

I don’t think Mad Men is ultimately cynical about these repeating patterns. Rather, it’s working with a (very tarot-friendly) metaphor of spiritual progress coming from a cycle that we have to repeat many times before escaping. It’s taking a similar angle to the central metaphor of Groundhog Day, a metaphor I’m particularly attached to. In the following six seasons the characters will live through many more versions of the destructive patterns they experience in “The Wheel,” but they’ll also face moments of clarity about those patterns, and sometimes find ways to break them. Mad Men doesn’t romanticize the process of change as a long exhale following a clear revelation, as filmed storytelling often does. Don will change, but it will be messy, humiliating, and frustrating, and he’ll fall backwards more dramatically than he’ll leap forward. He’ll cut back on his drinking in Season 4 and end up in a drunk tank in Season 6. Then he’ll try a little harder in Season 7. That’s how this stuff works.