The Lump in My Throat

March 7, 2014 - Features

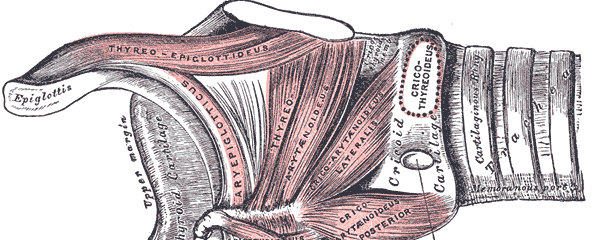

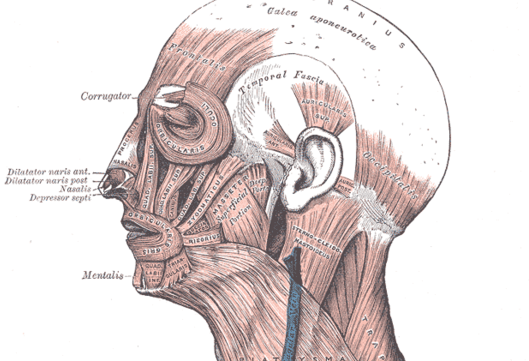

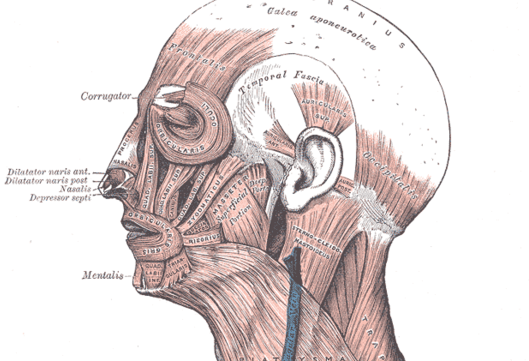

It starts up front. I push my tongue up slightly against the roof of my mouth and flare my nostrils a little, then draw the flaring motion upward to sort of spread out the muscles around my sinuses. I’m surprised every time by how much more easily I can breathe. The next step is a little harder. I move my attention backwards from the sinus muscles to the those at the very top of my throat, the ones that expand and contract when I breathe through my nose. I try to relax them, all the time testing how my breathing is changing. I find I often need to let go of an unconscious clenching of my jaw first. Every part of the system works together.

Then I move to the back of my neck. Compared to the more internal facial and throat muscles, these are easier to consciously relax. I can feel them with my hands and see how they work. It’s easier if I’m listening to the kind of music that makes me shiver. It’s usually sentimental and has lots of synthesizers. Some primal reaction formed in my 80’s childhood, I assume. I breathe in, then as I breathe out I let the shiver spread from the back of my head downwards. Little pinprick sensations run through my neck muscles and the tension in them eases a little. By now my sinuses and the top of my throat have tightened up again, so I take a breath and try to relax them all at once. I’m getting better at this.

The last step is the hardest. I try to relax the muscles in my lower throat that I use when talking or singing. As I relax the other muscles, the pain here has gotten more and more apparent. It feels just like a lump in the throat when I’m about to cry, only I seem to have it all the time without noticing it. I have no idea how to consciously relax these muscles. I swallow and breathe and shiver, but none of my tricks seems to work. A couple of times I succeed without knowing how, and the ache suddenly floods away for a split second. One of these times I immediately started sobbing.

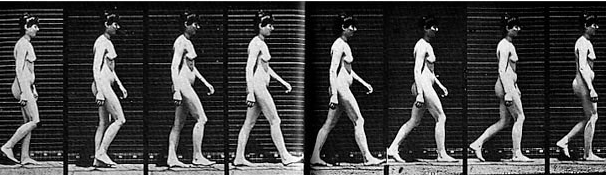

I always have little projects like this. There was the year I trained myself to stop crossing my legs and spread out my posture more while sitting. I trained myself to switch my internal monologue from second person (“What are you doing? You need to get to work”) to first person (“I need to get to work”). I spent two years analyzing and adjusting my gait when I walked. Years ago, I broke my habit of imagining conversations with people by distracting myself with ridiculous sci-fi stories.

It all sounds a little petty, but each of these changes was critical in improving some aspect of my mental health. The way I held and moved my body was an expression of fear, and changing the expression removed some of the fear as well. Thinking in the first person instead of the second prevented me from berating myself to the degree I was accustomed: “I’m an idiot” lacks the sting of “you’re an idiot,” at least to me. Curiously, it also mostly cured me of the tendency to accidentally talk to myself out loud in public.

Purging the imaginary conversations was the most important change of all. When I first started recording and analyzing the patterns in my bipolar disorder, one of the first things I noticed was that serious depressive episodes were always preceded by an increase in the frequency and emotional intensity of these imaginings. So instead of thinking about myself talking to people I knew, I though about fictional characters talking. Sometimes they talked about the same things, but somehow it was different. The intensity stopped escalating. The depressive crashes themselves were less severe when I managed to keep the conversations out of my mind. After eight years of practice, I didn’t even have to tell myself stories anymore. My brain had changed.

The new project is my throat. I first noticed it when I got a job with a driving commute. Naturally, this meant lots of singing along to the radio every day. And since I can’t do anything without critiquing my performance at it, I got frustrated at my singing. I was never musically inclined, but I’m pretty sure I used to be at least able to sing a song from start to finish, back in my school choir days. Now I could barely keep my breath during a verse, and there were all these notes I couldn’t hit anymore. I can go low or high okay, but as soon as I hit a specific range of notes in the middle my voice tightens up and cracks. It’s only occurring to me now that this happens to be the range of my speaking voice.

So now I spend my commute trying to relax the muscles of my throat. The way I’ve learned to open up my sinuses has been a revelation. I do it during panic attacks, and being able to breathe clearly, even temporarily, helps immeasurably. And I’m starting to have less pain in my neck, which is nice. But the vocal muscles themselves remain elusive. Now that I’ve noticed their tightness, I feel it all the time. The way I run out of breath when I’m speaking, for example, or how much my throat hurts after interacting with people. The way my voice gets scratchier and harder to understand the more nervous I get. The way I can be getting into a nice groove singing, then the moment I mess up a lyric my voice breaks. I can feel the muscles lock up now. Every time I get scared, I strangle myself from the inside.

The few times I’ve managed to relax them, it feels like a floor dropping out from under me. It’s nauseating. But for a second, it feels like I’m singing straight from my lungs, and it’s amazing. It never lasts long, at least not yet. But it will. I’ve been through this process enough times to know when I’m breaking a muscle down.

When I was a teenager, I read a lot about tarot cards, and consequently a lot of New Age stuff. One bit of the philosophy stuck with me: “as above, so below.” As I interpreted it, it meant the nature of a thing is reflected in its smallest parts. A fearful creature is fearful not just in its mind and spirit, but in its hands and fingers and skin and atoms, all the way down. To me, that also meant that you could affect the nature of a thing by changing its smallest parts. Remove the fear from the fingers, and there’s less fear in the spirit. Later I would encounter the same idea in a more scientific form as embodied cognition, and feel a thrill of recognition. Whichever version appeals to you, if either, it’s a belief that’s served me well.

The way I’ve survived over the years is by paying attention to the patterns of my mind and what factors affect them. I write down what I’m thinking, I test out changes, and I try to keep myself separate enough from my emotions to see where they come from. It’s not perfect, but it works for me. I wrote about all this some in my Arcade Review article on Groundhog Day games. But an equally important part of this process was learning to change small things. Trying to change big patterns was always disastrous for me. I couldn’t stop my inner voice from yelling at me; that just taught me to yell at myself about how much I yelled at myself. I could, however, change the voice’s grammar. Somehow that helped. I couldn’t stop being afraid, but I could change my posture. The small things are important, and everything is connected. Right now I’m just relaxing muscles, but I’m relaxing muscles that keep me from speaking. This is how I’ll find my voice.