Ending vs. Resolution

September 5, 2011 - Features

Red Dead Redemption

According to a recent CNN story by Blake Snow, only 10% of players finish the games they start. This being an article from a major news source, there was no information on the origin or accuracy of this statistic beyond a couple of guys saying, “Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard, something like that.” Nonetheless, it provided a platform for several nearby game developers to ruminate on what it all meant for the future of the industry. The article also caused something of a tizzy in the gaming blogosphere. People are trying to figure out what we’re doing wrong, how to fix it, and whether there are better metrics for engagement. Meanwhile the comment threads are full of players deriding either the quality of modern games or the inferior moral fiber of the non-finishers.

The statistics in the CNN article may be pure fiction, but they kicked off a real debate. Do people really not finish games? If so, why not? This question has often been buried in posturing, however. The original article, for example, very much takes the position that this is a black eye for the games industry. “Let that sink in for a minute,” Snow writes: “Of every 10 people who started playing the consensus ‘Game of the Year’ [Red Dead Redemption], only one of them finished it. […] Who’s to blame: The developer or the player? Or maybe it’s our culture?”

Maybe it’s our culture, you guys!

If you step back, this “who’s to blame” framing is pretty weird. Plenty of people have brought up the point that many popular games, including puzzlers, MMOs, simulations, sports games, and multiplayer shooters, aren’t meant to end at all. Even in a story-driven game like Red Dead Redemption, it’s not immediately obvious that not reaching the ending is a big deal. After all, Redemption is a sandbox-style game, and some players might like the game but not care for the main quest.

This outrage seems to result from inappropriate expectations being imported from movies and books. “I walked out before the end” is the gravest insult you can give a movie. That’s hardly a universal standard for artistic experiences, though. If you leave a great building before seeing every room, did it fail at being engaging architecture? If you pick out a few favorite songs from an album to add to a playlist, did the musician do something wrong? How long do you have to stare at a painting before you’re finished? Lots of people consider Twin Peaks to be a great TV show. Almost all of them will urge you to stop watching before the end.

Outside of a theatre, it’s normal to be selective about how much of a work we experience. The CNN article and its responses have tried to explain why people don’t finish games, but by assuming it’s a problem to start with, they’re stuck picking at aspects of the industry they don’t like. If you get away from the issue of blame, this is actually a valid question. Is there something about games that makes people not want to finish them?

I argue that there is, and it has a lot more to do with basic narrative structure than with “things getting boring in the middle.” There are narrative theorists, notably Northrop Frye, who see all classical storytelling as essentially about the conflict between a hero and the world he or she lives in. The hero wants to do something, society or natural law prevents it. The hero has to either change the world (comedy), learn to live with it after seeking adventure elsewhere (romance), be overcome by the world (tragedy), or change the world only to make things worse (satire).

All of these storytelling modes assume that the hero starts out in conflict with the world. The hero is someone who disagrees with society’s rules, or doesn’t belong, or has a goal the world can’t allow. By the end of the story this conflict is resolved one way or another. So what happens if this conflict is never there? If the hero was always an absolutely perfect fit for the world, how do you even start to tell one of these classical stories?

This is the problem most narrative games have. The cutscenes and other fixed elements might tell you that you’re a scrappy underdog, fighting against all odds. The writers may try to create a fictional world in conflict with your character. But everything else in the game tells you that, to the contrary, you are the one person most in tune with the universe of the story. You are the most competent character in the world. You understand its rules better than any of the poor little AIs you encounter. You even have the ability to go back in time and change your actions, giving you a godlike perspective on how your decisions affect the story’s events.

In most narrative games, the world and the hero aren’t in conflict. They’re soul mates. You can tell me all you want that people don’t trust me and my mission is hopeless, but at the end of the day, I will always succeed. No amount of writing can counteract this.

It’s a problem that touches on Paul Sztajer’s half-Cinderella argument about game stories. Sztajer writes that game stories are incomplete because they never inflict hardship on the player, narrowing the kind of story arcs that can be told to those where you start out weak and get stronger, The End. The half-Cinderella is another consequence of the lack of conflict between world and hero. The only real story arc that’s possible in this situation is one where the hero doesn’t know the world very well at first, and gradually gets better acquainted with it. Not exciting, but maybe pleasant if the world is charming enough.

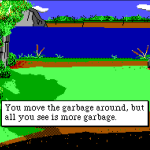

Wait, what? Fallout 3’s graceless ending.

If game endings are generally not satisfying to players, I suspect that this is why. If there was never any conflict in the beginning, that conflict can’t get resolved at the end. No resolution means that the world just stops, and who wants that? That world is your soul mate! It’s like watching a beautiful love story where one of the partners drops dead for no reason right before the credits roll. Audiences would probably be furious, as players were when Fallout 3 provided an especially egregious example of this kind of non-ending ending.

There are two basic ways out of this problem. One is to create greater conflict between the player and the game world. This can mean increasing difficulty and opportunities for failure. Of course, this will do nothing if every failure means you die and reload an old save game. The result of that is that the canon version of your character is still in perfect harmony with the world. The game would need to allow actual failure that affects the storyline. This is essentially what Sztajer is arguing: provide the player with genuine hardship, and you can start telling real stories.

The other solution is to embrace the goofy love story between the hero and the world. This means you would treat the game world as a character, and find some other source of conflict to keep the hero and the world apart. The closest thing I’ve seen to an implementation of this is Fable, where the other heroes act as romantic rivals between you and the society that will eventually learn to adore you. Fable is basically a romantic comedy from this point of view, but there are presumably many other approaches that can be taken. This would be a much stranger approach, so I’m personally in favor of it.

Acknowledging that people don’t always finish games doesn’t have to be a terrifying experience, as it seems to have been for many writers. It can also be a useful data point in figuring out how people interact with game stories and why. Many game stories don’t need endings. Those that do would benefit from serious analysis of what that ending does and does not resolve.