Guess What I’m Thinking About

June 20, 2011 - Features

I find room escape games kind of unsettling, for reasons I have trouble putting my finger on. Room escapes are a popular casual gaming genre that offer Myst-like puzzling in a short form. You’re stuck in a room and need to get out. So you find some keys, crack some simple codes, and combine objects until all the doors are open. They usually take ten to twenty minutes and are rarely taxing. They’re not the kind of thing that should cause a lot of anxiety.

I think my reaction to these games has something to do with how I feel about adventure game puzzles in general. I define adventure puzzles as any puzzle where you have to perform a specific sequence of discrete environmental actions in order to progress in the game. (That’s a definition with some fuzzy boundaries to it, but it’ll do for now.) The distinctive feature about adventure puzzles is that they require you to guess what the designer wants you to do, as opposed to formulating a plan of action on your own.

Of course, if a plan you make happens to be what the designer expects, this distinction vanishes, and the gameplay feels more natural. People praise adventure games where the puzzle solutions seem to follow logical patterns, and bitterly condemn those where the designer’s train of thought is baffling. Most adventure puzzles, including those in typical room escapes, fall somewhere in between these extremes. You might be confused for a while, but once you figure out the solution, you can see what the designer was getting at.

It’s in that period of confusion that adventure games can start to feel kind of creepy. You’re in a strange environment and you don’t know what the rules are. Someone expects something of you, and their presence looms over your shoulder while you poke and prod at various objects. You’re engaged in a mind-reading exercise with someone who might seem a little insane at times. It’s no coincidence that the most successful horror movie franchise of our time, Saw, is basically a series of gore-splattered room escape puzzles.

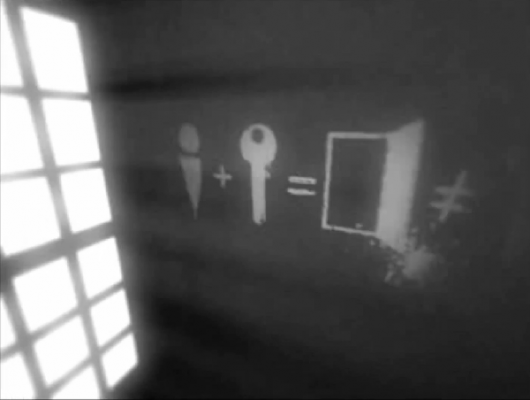

Mike Inel’s Which is a short experimental game that takes the inherent creepiness of room escapes and dials it up in some clever ways. For the most part, it follows all the basic conventions of the genre. You find some keys and a screwdriver, you open up lots of drawers, and you decipher odd clues written on the wall for some reason. There are no complicated puzzles. But the presentation is designed to amplify anxiety.

The graphics rendering is in high-contrast black-and-white and overlaid with heavy static, turning the environment fuzzy and ambiguous. There is strong lighting just around your position as well as far away, but in between there is a band of darkness. The effect is that objects drop out of visibility as you approach them, only to reappear when you’re right on top of them. This is a bit of a crude technique, but it’s also a clever way to bring something like horror-movie editing into an interactive environment.

The thing I found most unsettling, however, was the huge amount of empty drawers and cupboards in the game. In conventional room escapes, every door you open will have something useful behind it. The rhythm of the game comes from opening drawers that help you open other drawers until you finally get to the exit. In Which, only one of the many cupboards and drawers you can open has anything useful in it. The rest just hang open, empty and unreadable. Including a bunch of purposeless interactive objects in a game like leaves the player scrambling to guess what she’s supposed to do. I kept expecting something to jump out at me from one of the cupboards. But I kept opening them because, well, that’s what you do in room escapes.

Then ending of the game doesn’t quite live up to the queasy weirdness of the first half. I had a similar problem with Penumbra: Overture; horror games still haven’t quite figured out how to stay scary after showing the monster. But Which still gets major points for tapping into the frightening aspects of an otherwise innocuous genre of casual games.

[Note: This post originally appeared at Robot Geek. I’m gradually backing these up here.]