The Hostile Guide

June 7, 2011 - Features

[Note: This post originally appeared at Robot Geek. I’m gradually backing these up here.]

Spoiler alerts: Bioshock, Loved, Mass Effect 2, Memento, Portal, Seven Minutes, The Usual Suspects.

The recent release of Portal 2 has rekindled the world’s love affair with GLaDOS, the chirpy AI who delivers instructions and insults throughout the original game. GLaDOS represents a character type which is interesting because it is so unique to videogames: the hostile guide. Characters who act as guides are common to all types of stories, particularly those that take place in an unfamiliar or fantastical setting. A character with special knowledge about the world, like Obi-Wan Kenobi or Gandalf, can help explain things to both the hero and the audience, define the quest, and offer magical aid to get the hero out of awkward situations.

Guide characters are useful to game designers, since games often involve an unfamiliar world that the player must learn how to navigate. Having a character do this teaching can in theory create a smoother experience than reading a tutorial or manual. Guides in games range from tutorial text with a name (like Navi in The Ocarina of Time) to full characters with subplots of their own (like Otacon in Metal Gear Solid 4), but usually, they’re on the player’s side.

The hostile guide is a variation on this character type that has an antagonistic relationship with the hero. That is, the character telling you how to play the game is working against you somehow. This can make for a pretty weird dynamic. In Portal, it’s mostly played for laughs: GLaDOS’s instructions become increasingly passive-aggressive throughout the first half of the game, and outright bitchy after she unsuccessfully tries to kill the player. Likewise, the item-shop sim Recettear treats the relationship between the hero and her loan-shark guide as a mildly antagonistic buddy comedy. But it can also be played as a dramatic betrayal, as in Bioshock, or a source of paranoia, as in Mass Effect 2 or Shadow of the Colossus. Hostile guides can be as varied as antagonists are.

These versions of the hostile guide have their counterparts in other media, especially in twist-ending movies. The Usual Suspects and Memento each memorably feature a character that seems to guide the hero through a baffling world but really has his own sinister agenda. This similarity exists because the hostile guides in these games are antagonistic in the game’s narrative, but not in the game’s mechanics. GLaDOS, “Atlas”, and the Illusive Man may not have your character’s best interests at heart, but with rare exceptions, their instructions genuinely help you progress through the game. Similarly, Teddy’s explanations of Leonard’s condition genuinely help the audience understand what’s going on in Memento, up to a point.

Mirosurabu’s depict1

The hostile guide gets really interesting when this isn’t the case. The most extreme example can be found in Mirosurabu’s experimental short depict1. Here, every instruction the guide gives you is the opposite of what you should be doing, and following its instructions will invariably kill you. The gameplay is about figuring out the rules without being distracted by the instructions. This makes for an unusual type of challenge, but the experiment doesn’t go much further than that.

Two other experimental games do take the idea further. In Alexander Ocias’s Loved, the hostile guide is used as a metaphor for an abusive relationship. I’ve written more about the game elsewhere, as has Dan. The idea is that following instructions makes the game easier, but those instructions are arbitrary, demeaning, and will sometimes get you killed. Not following instructions makes the game progressively more difficult, and therefore that much more satisfying if you do win. It’s a complicated dynamic that wrings a lot of emotion out of a simple gameplay mechanic.

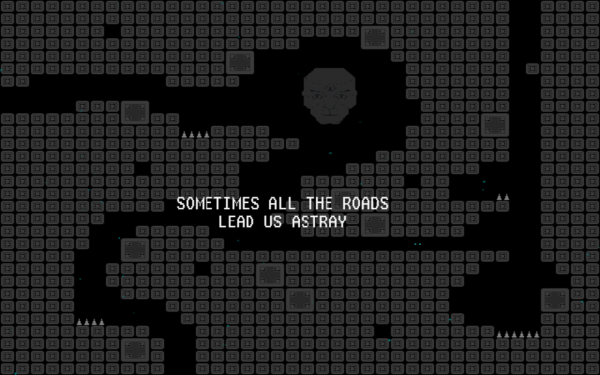

Tuukka Virtanen’s Seven Minutes

Tuukka Virtanen’s Seven Minutes is another short platformer that uses the hostile guide in an unusual way. In this case, the guide spends the entire game telling you not to progress, and insisting that you made a horrible mistake by leaving the first screen. If you listen to him and stay on the first screen, you are told at the end that you won; but if you ignore him, you get to actually play the game. This is an antagonist that isn’t just opposed to some goal the protagonist has within the story, but to the telling of the story itself. This is a trick that would be difficult to pull off in a novel or movie without being unbearably pretentious, but Seven Minutes demonstrates that it can make for fun, witty gameplay.

One thing that stands out about the hostile guide is that the previously mentioned triple-A games that use it – such as Portal, Bioshock, and Shadow of the Colossus – are among the most critically acclaimed games of recent years. Something about a game built around this kind of character is really appealing to people.

This could be because the hostile guide in games does something that can’t be done in other media. It takes the sense that you, the player, are at war with the game, and turns it into a plot point. Players often feel a little aggressive towards the game world they are exploring. They want to break it, test its limits, and do whatever they want. The constraints that prevent them from doing so can lead to resentment if the player doesn’t buy into the game completely. The hostile guide takes that feeling of resentment at being dragged around from mission to mission and makes it part of the story.

Hostile guides in movies can make you feel sympathy towards the deluded hero, but it’s not the same thing. Those aren’t feelings that are basic to the experience of watching a movie. The hostile guide is a narrative trope that is relatively uniquely to videogames, and those are always exciting to find.