Daniel Benmergui and the Gulf of Execution

July 12, 2009 - Features

In the study of human-computer interaction, a user’s uncertainty about how a system will respond to her actions is sometimes referred to as the “gulf of execution,” in Donald Norman’s phrase. In useful software, of course, a designer tries to narrow this knowledge gap as much as possible, and the same is true of many videogames. But Daniel Benmergui seems to be generally interested in aesthetically exploiting it. In the three short art games he released this year as a package, he widens the gulf of execution in subtly different ways, and with varying effects.

In Storyteller (2008), your manipulation of the characters in each the three segments of the story results in unexplained changes to the other segments. It’s left to the player to infer the narrative rules at work, an inference which is forced by a player’s natural inclination to understand the rules of the game she is playing. The proposed set of storytelling laws the player uncovers, it is implied, may be inferred from other fairy tales if the reader puts the effort into it. In this case, the distance between action and result is mainly used as a prompt to the player’s imagination. This effect is not an unusual one in games; indeed, figuring out why doing this should have caused that makes for much of the enjoyment in god and tycoon games.

A more idiosyncratic use of the gulf of execution technique is at play in I Wish I Were the Moon (2008). Unlike in Storyteller, the interaction method in this game is itself highly indirect. The “movable snapshots” metaphor introduces another level of uncertainty to the relationship between action and results, since it is not only unclear what your actions will do, but also which of your movements may be considered actions. Some objects can be moved with the camera, some can’t: you can move stars and people, but not boats or moons. A single object, the shooting star, can actually be multiplied with the camera. What can be done is unpredictable, as well as what will result from what you do, and whether anything will result at all. The gulf of execution is vast in this small game, giving the player a direct experience of the distance and frustration felt by the characters.

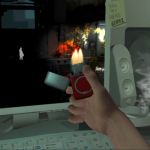

Today I Die (2009) partially adopts the direct manipulation of objects present in Storyteller, but adds a different kind of indirectness by introducing text as a special kind of game object. Essentially, the text allows the player to manipulate the game’s environment as well as its objects. The gulf here is not as wide as in I Wish I Were the Moon, since the interaction is more immediately responsive, but in a sense it is broader; your actions continue to be leaps in the dark, but now they can affect the entire environment. This gives Today I Die an unusual sense of instability.

The real elegance of the game comes from the alternation of global and local actions: you manipulate objects to get a new word, using the new word gives you new objects to manipulate, and so on. The rhythm of great and small leaps that results lends the game a sense of nervous exuberance. I suspect that this control of rhythm – not an easy thing to achieve in games – has much to do with the frequent description of Benmergui’s games, Today I Die especially, as “poetic.”